Risking a zero: Fraud, Ponzis, and $BRK

What’s an acceptable risk for fraud when you make an investment?

For a lot of people, I think the answer would be “Zero! I want zero risk of fraud in an investment!” That’s an easy gut answer… but take a detour with me for a second.

In The Snowball, Buffett somewhat famously said that his returns in the early days were so good that a lot of people thought he was running a ponzi scheme. This story got a lot of play, particularly around the Madoff scandal.

Investing is a funny game in that, because of the power of compounding, your greatest mistakes will generally be ones of omission, not commission. With a decent amount of time, one spectacular investment will overwhelm quite a few mistakes, and the lost returns from missing a multi-bagger will be larger than the losses from one poor investment. Buffett noted that passing on investing in Walmart was ultimately much more harmful to them than their awful investment in Dexter (see p. 11).

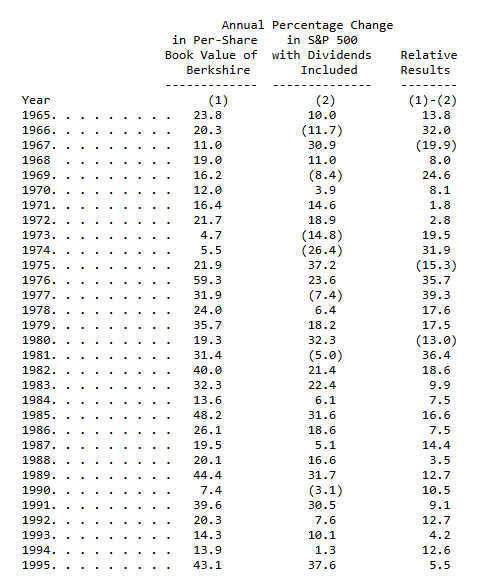

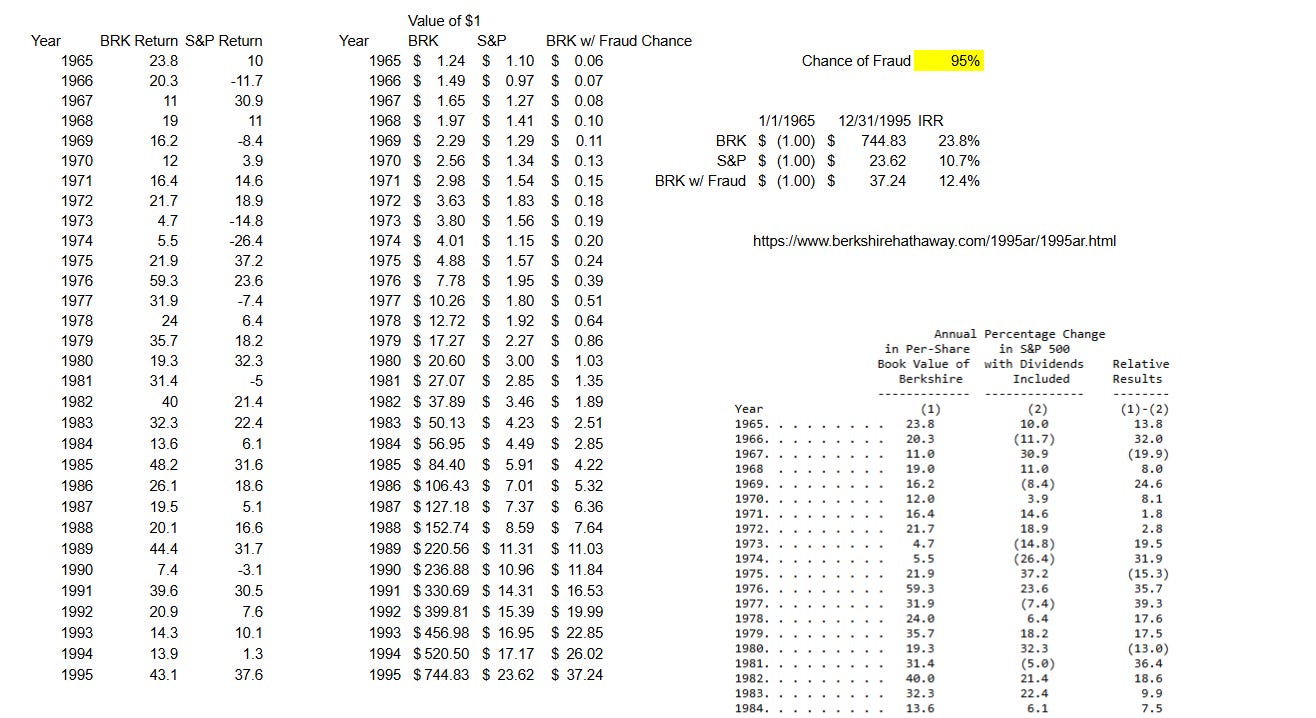

So let’s rewind the clock a bit and engage in a hypothetical. From 1965-1995, Berkshire1 goes on an insane run; book value compounds at just shy of 24%/year while the S&P (with dividends) does ~10.7%. $1 invested in Berkshire turns into just shy of $750 at the end of those 31 years; in contrast, a dollar in the S&P turns into just shy of $24. Again, insane.

Now pretend that we rewound the clock to 1965 and I gave you the option to invest into Berkshire with one catch: there was a chance that instead of investing in Berkshire you were investing in a Ponzi scheme and would lose all your money. What percent chance could you take and still have Berkshire outperform the S&P 500?

5 percent? 10 percent?

Nope.

Berkshire’s run is so epic that you could take a >95% chance of it being a complete fraud and you’d still outperform the S&P over the next 30+ years. A 5% chance of getting a 24% annualized return over that time frame and a 95% chance of a zero still come out to a ~12.5% IRR, leaving you with ~$37.20 of expected value at the end of the run versus the ~$23.60/share you’d end up with from buying the S&P.

Of course, we can and should caveat the heck out of that analysis. Nothing on this blog is investing advice2, but I sure as heck am not advocating for anyone to go plow a bunch of money into potential frauds on the thesis they just might be the next Berkshire! And our analysis assumed we knew for sure that the investment we made would either be the next Berkshire (almost literally the best investment one could have made) or a complete zero; if you changed the upside of that analysis from “the best possible multi-decade compounder” to “a well above average 30 year return”, then the whole thing fall apart. And I’d note that it assumes a very, very long time horizon; yes, your expected value if you can buy Berkshire is higher than investing in the S&P over a ~30 year time horizon even if you have a 95% chance of investing in a zero….. but your expected value doesn’t flip positive versus the S&P until about year 26. You’re not even breakeven on your investment (in expected returns) until year 15! Every investor claims to have a long time horizon…. but I somehow doubt any investor has a time horizon so long that they could justify 26 years of underperformance!

I realize I just threw a ton of numbers out there, so here’s a screenshot of the number I’m playing with….

… and here’s the (quick) Google Sheet I used to create those numbers. You can copy that sheet / play around3 with it if you want to recreate the numbers or change the assumptions. Simply change the yellow box in cell n4 to whatever odds of fraud you want and you can see how the IRR / money grows over time with those assumptions (and obviously you can make wholesale changes through the rest of the sheet if you want to play with other assumptions). Again, assuming that you are guaranteed a Berkshire like return or a complete zero is pretty stark, but I do think it’s an interesting illustration of how insane compounding at super high rates can be over time!

Anyway, to bring this back into the real world, why have I been thinking about fraud and zero risk?

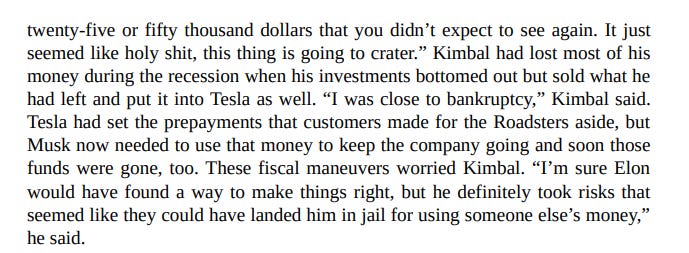

I spend a decent amount of time looking at smaller cap / growthier companies. I don’t invest in many, but I do look at a lot of them! And, as my friend Artem Fokin likes to say, when you’re investing in a great growth company that can compound at above average rates for decades, you are by definition buying an outlier. When you’re buying an outlier, you’re hoping you’re buying a positive outlier but there’s some risk that the company turns out to be… not an outlier, or even a negative outlier. There’s a risk the company was a flash in the pan, or overhyped, or even just a flat out fraud. And often these risks go hand in hand with what makes the company a potential outlier: outliers outperform because of weird quirks, and the line between “weird quirk that leads to outperformance” and “weird quirk that’s a symptom of something much more sinister” is really thin. In fact, often the difference between the two is simply “was the company successful”; for example, Elon Musk is one of the richest and most powerful people in the world today, but there’s almost certainly an alternate timeline where all the risks he took around Tesla and SpaceX landed him in jail:

Often when I look at these growth companies, I’ll see some red flag or quirk or risk and instantly pass…. but I’ve been wondering if my risk barometer has been turned too high. If I see some risk and there’s a 1% chance the company is a fraud but a 25% chance it’s the next NVDA, then I’m costing myself a lot of money by passing on it!

So what is the appropriate answer? What’s the appropriate tuning?

Honestly, I don’t know. The answer varies based on a lot of factors, including the upside (if there’s a chance of the company being a fraud and a chance it’s the next Tesla, that might be a risk worth taking! If there’s a chance of fraud and a chance it’s a slightly above average performer, that’s an instant pass!), the odds of downside, and the individual investors personal taste / preferences.

But it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot. And it’s still a work in progress for me.

PS- One of the reasons I’ve been thinking about this is because of the podcast! Every now and then someone will want to come on and pitch an interesting company that has some smoke / red flags around it, and I never know what to do with those potential pitches. Generally the company and thesis is really interesting; is it worth having the company on and discussing the issues in a level headed way? Or is it not even worth the headache of having that discussion if the company turns out to be a turd? What level of risk is too high to discuss a turd? 50%? 5%? I’ve generally leaned towards having a high risk tolerance and trying to have a discussion in a level headed way, but increasingly I’m thinking a lower risk tolerance might make sense on a free / publicly available podcast! Again, work in progress / always open to hearing other views.

PPS- this is the first in a loose series on tail risks and zeroes. I have at least one and as many as three more in the series planned; I will update this post with links to them when available. (editor’s note: part 2 (Risking a zero: tail risk, disruption, and Malone) is live here)

PPPS- Another area I’ve been thinking about upside and zero risk is how it relates to disruption. I’ll have more to say on that in a bunch of future posts, but for now just wanted to highlight that AlphaSense was kind enough to sponsor a free webinar with a payments expert (a Mastercard former) to how Stablecoins could impact the sector; it was a really interesting conversation, and it goes live Tuesday (you can find an early peek at a discussion on stablecoins here). If you’re interested, you can sign up using this link

Disclosure: a small position in BRK

I have that sheet locked, but simply copy it into a new file you control and you can make all your own changes!

I get that it is all a 'hypothetical' here, but a 30 year fraud is tough to believe in. What would be the suggestion in ~1965 that a fraud was 95% probable? At the extremes, everything is upside down, divorced from the intended logic of statistical probabilities. This merely serves as a framing point for dialing in your logical tolerance for uncertainty, but you don't have a framework for that, only an acceptance that 26 years into BRKA, and 26 years into believing BRKA could still be a fraud, you'd have an internal downside risk of matching the market?

life seems pretty miserable when 'not yet rich enough' is perpetual.