Missing a bidding war: a mea culpa on Metsera ($MTSR)

A small post-mortem on a big missed opportunity

If you read a lot of merger proxies, you’ll notice there’s a funny recurring bit in a handful of proxies for strategic deal targets: the winning bidder is often not the highest bidder.

Why?

Because the highest bid often comes from the largest strategic buyer and thus carries some anti-trust risk1, and boards often chose to favor certainty of closing over the highest price2 and thus go with a lower bid that carries no anti-trust risk.

An example will show this clearly. In early 2021, CoreLogic announced a deal to be acquired for $80/share by Stone Point and Insight. CoStar quickly submitted a topping bid3 which they soon bumped up again. Despite the CoStar bid being a premium to the Stone point bid, CoreLogic chose to decline CSGP’s offer because of regulatory uncertainty (as well as favoring certainty of value from the Stone Point cash bid versus uncertain value due to the volatile nature of CSGP’s stock (which was part of their bad)).

That’s a light historical example. There’s another example in the public markets right now. Pfizer announced a deal to acquire Metsera4 (MTSR) for $47.50/share plus a CVR in late September (per the proxy, the all in value of that offer is ~$54.66/share; see p. 45). If you read the MTSR proxy, you could see that there was actually a higher bid for MTSR; page 44 of the proxy notes that “party 1” had made an offer that was valued at $59.46, but the board determined to go with the Pfizer offer for a variety of reasons, but most notably “potential regulatory risks5.”

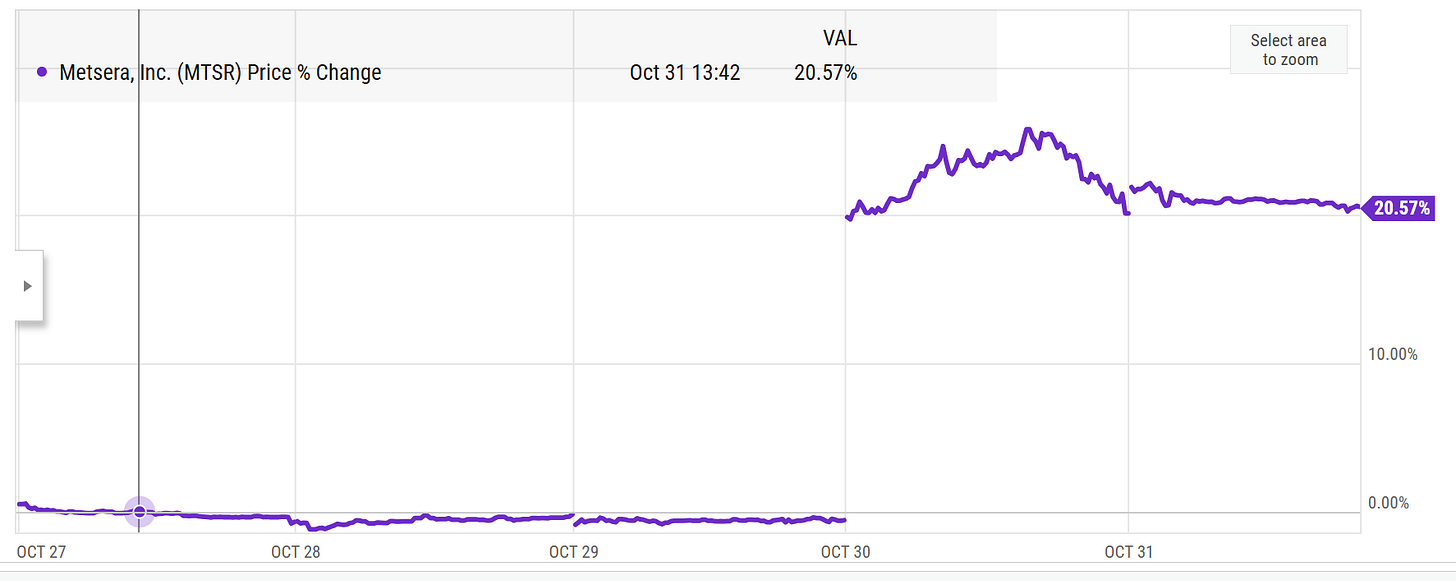

That proxy background got really interesting earlier this week, when party 1 (Novo Nordisk) lobbed in an unsolicited proposal to buy Metsera that was deemed a superior bid (over Pfizer’s strong objections, including a lawsuit filed Friday night!). The superior bid and prospect of a bidding war sent Metsera stock up ~20%. Not bad for a merger arb!

Now, there are all sorts of interesting things about the Metsera / Pfizer deal; in particular, I’d note that the structure Novo is using to sidestep anti-trust risk to the deal is extremely novel6, though the potential for a bidding war for a strategic asset is also interesting. If you wanted to get really galaxy brained, you could think about what the intense competition for MTSR shows about what big pharma believes for the future of GLP1s, or perhaps you could think about what other public companies have similar assets that might be attractive as a consolation prize to whoever loses the MTSR bidding war.

All of those lines of thinking are very interesting…. but I’m not writing this article to talk about any of those.

So why am I writing this article?

Because the MTSR set up was right in the middle of the strike zone for me, I missed it (I didn’t have a position into the superior offer), I’m pissed at myself for missing it, and selfishly I kind of wanted to rub my nose in it…. but even more selfishly I find that publicly highlighting the types of set ups I really like often leads to future inbounds along the lines of “hey, you said you liked the MTSR set up, this kind of reminds me of it; have you looked?” and I’d love to plant that flag out there as well!

Let me back up a bit. I recently did a post on “no lose” set ups7: situations where the only two outcomes (outside of an extreme tail case) is you either break even or get a premium. And the MTSR set up fit into my favorite type of no lose set up: a potential topping offer or strategic bidding war that you weren’t paying any upside optionality for. That set up is extremely rare and very lucrative. Again, right in my strike zone; missing it feels like a crime.

Let’s set the stage by discussing the downside of this set up. You couldn’t have bought MTSR a week ago and known a topping bid was coming. However, you could have known that you weren’t really risking much when you bought the stock. MTSR closed on Wednesday (the day before the Novo bid) at $52.21/share. MTSR was getting bought out by Pfizer, and the deal was scheduled to close before year end. The Pfizer deal value consisted for $47.50/share in cash plus a CVR for MTSR; the proxy said the fair value of the total deal was $54.66/share. Could you quibble with the valuation of the CVR? Sure…. but given so much of the deal’s value came in cash arguing about the CVRs value in that context is kind of splitting hairs (the CVR clearly has some positive value!); I don’t think I’m being over the top to say that MTSR’s stock before the Novo bid was announced wasn’t pricing in the possibility of a topping bid.

So, before the Novo bid, the set up was pretty simple: you had a company getting taken out by an A+ buyer (short of Berkshire Hathaway, Pfizer is probably the best buyer on the planet) with limited time to deal close, basically no antitrust risk, etc. That’s about as good of a “no downside” bet as I can think of.

Now, a pessimist might argue “hey, Andrew, sure that sounds like limited downside, but you couldn’t have known that Novo would come over the top. There was no go-shop here; isn’t dragging yourself through the mud for missing this akin to kicking yourself for not predicting the future?”

And I think the answer there is clearly no, you could have predicted there was at least some chance8 that a bidder was going to come over the top for MTSR, and given the market price for MTSR was at or slightly below the fair value of the Pfizer deal you were picking that upside optionality up for free.

Why do I think you could have predicted a possible topping bidder?

Because the presence of a higher bid was right there in the MTSR proxy.

MTSR’s proxy came out October 17th. It discloses that party 1 (who we now know to be Novo) offered a package valued at $59.46/share (see p. 44) for MTSR. As mentioned above, MTSR ultimately turned down Novo in favor of the certainty of the Pfizer deal.

You’ll recall I mentioned earlier that boards often turn down higher bidders with some type of regulatory or financing uncertainty in favor of a lower offer with more deal certainty.

But bidders and boards often differ quite a bit in their assessment of risk. The funny thing about public companies is that they are required to file a proxy with the background of a deal, and bidders who were passed over can then read the proxy and say, “huh, the board was concerned about that? We think they were completely wrong” or “o, we didn’t realize this one item was a gating factor for the board; let’s fix that issue and go back with a better bid.” And, even if the board still thinks the offer is inferior, the higher bidder can always take the question directly to the company’s shareholders, and shareholders will very often let the board know they’d prefer the higher price and antitrust risk to the certainty of the lower price.

So MTSR fits into a unique and perhaps my favorite of all of the no lose set ups: a merger arb that is scheduled to go through where there is a publicly confirmed strategic that has offered a higher price and was turned down for some reason. The reason this set up is so interesting is the spurned bidder can wait, read the proxy, see all of the companies projections, see what the company was worried about when it came to antitrust, see what other bidders were bidding….. and then chose to swoop in at the last second with nearly unprecedented amounts of information!

Again, this set up is rare…. but time and time again I see that the market underprices the odds of a topping bid from a bidder who was offering more and got passed over for some reason (generally anti-trust9). Let me give a few examples:

My favorite example is Disney / Fox. They announced a merger in late 2017 that valued Fox at about $28/share (plus a spinoff)…. but then a few months later Comcast swooped in with a $35/share offer, and Disney eventually bumped their bid to $38/share. So, If you had bought Fox stock the day the initial deal was announced, you’d have made ~35% in ~6 months through the course of the bidding war…. and, if Comcast had never shown up, you’d have still made a normal arbitrage spread!

How could you have known that Comcast might come in over the top. Well, there were plenty of press reports that Comcast had been trying to buy Fox with a higher offer before Fox sealed the deal with Disney…. but you also could have read Fox’s initial proxy in late May 2018 and seen / confirmed that Comcast had made a much higher offer for Fox! Again, that proxy came out late May 2018…. Comcast made their (public) topping offer a few weeks later.

Chevron announced a deal to buy Anadarko for $65/share in mid-April 2019; right when the bid was announced David Faber reported “Occidental was prepared to pay $70 a share for Anadarko and is currently exploring its options.” Anadarko traded slightly below the Chevron price when the deal was announced…. Sure enough, Occidental came with a topping bid less than two weeks after the Chevron bid was announced and eventually won that deal (I believe Andarko’s stock closed at $73.39/share when the definitive OXY deal was signed ~a month later, so that’s a very nice bump insider of a month…. btw, OXY’s CEO does not come off well in the Anadarko proxy).

Marriott and Starwood announced a deal that valued Starwood at ~$71/share in November 201510. Starwood was a very hot commodity and there were plenty of rumors that other strategics were looking at buying it; those rumors were confirmed when the proxy came out in February 201611. It disclosed nearly unlimited strategic interest in Starwood’s portfolio, but in particular I’d note that Company G and Company F both sent offers to buy Starwood for $86/share that were dismissed for one reason or another. Sure enough, in March Anbang offered $76 and then $78/share, their bid was deemed superior, and Marriott eventually had to bump their bid to $79.53/share (or $85.36 if you included the value of the spin).

One thing that was/is so unique about the marriott / starwood set up? Marriott’s CEO was acknowledging the potential for a bidding war when the deal was announced; this FT article from right after the initial deal was announced has an incredible quote from him, “Will other bidders crash the deal? We hope they won’t.” The article goes on to speculate that Hilton, Hyatt, IHG, or several Chinese companies could serve as interlopers.

In a deal that still causes me nightmares, Spirit chose to merge with Frontier despite a superior offer from JetBlue. JetBlue was not happy about that decision and went to war to get Spirit…. JetBlue would ultimately win that war but lose the “asset” in a travesty of an anti-trust decision (I will admit significant bias there).

I’ll note I said “let me give a few examples”…. but I both looked through ~10 years of my own notes12 and had chatgpt do a search as well, and these were the only four examples this set up I could find in the past 10-15 years. Metsera / Pfizer / Novo will take my data base to five. Basically, you can expect to see one of these set ups every 2-3 years13.

I am sure I am forgetting a few examples of this set up working…. and I’m also sure I’m committing some type of survivorship bias where I’m only looking at examples where the set up worked / resulted in a higher bid and ignoring all the times where the proxy disclosed a higher offer but the bidder never came back with a superior bid so the deal just closed on normal terms.

But my overall point is this: these types of set ups are extremely rare. To miss one of those set ups is borderline unforgiveable, at least in my mind, and I’m kicking myself for it. I’ll try to do better in the future (and, of course, if you ever see one and want to chat, my DMs are always open).

Odds and ends

Is MTSR interesting from here? Maybe! I take no real view. If you read the proxy, it does seem like every bidder was getting pushed to their limits, so I’d be surprised if there’s a ton of upside here14…. but this is clearly a strategic asset, and Pfizer is literally suing to hold on to it. You could imagine all sorts of machinations to bump the deal up and get it over the finish line from both sides….. but, again, I’m not taking a view here; this article was about the set up and missing it before the first topping bid, not playing a potential bidding war going forward.

When people are reading this article, I’m sure they’ll note a bunch of examples that seem similar to this set up…. but I think many of the examples would fail to match up to the unique fact pattern here. What makes the MTSR (and other examples listed) deals so unique is you have a strategic target with a strategic buyer and a publicly disclosed higher bid from another strategic that was dismissed for some reason (preferably anti-trust related). That is a very rare and powerful example; let me contrast it with two other set ups that, while still interesting, aren’t quite as good / rare in my opinion:

General bidding wars: Bidding wars are very rare, and there’s nothing like being long a company that gets involved in a bidding war…. but, while it would be great to get caught in one of them, you cannot know the future. What distinguishes this MTSR style set up from a general bidding war is that we had an SEC filing that confirmed the presence of a higher bid. Contrast this to, say, the greatest bidding war ever: the Verizon / AT&T battle for straight path that saw T enter an agreement to buy Straight Path for ~$95/share and, after a series of topping bids, eventually had Verizon end up buying Straight Path for $184/share. Would it have been awesome to be long Straight Path through that whole bidding war? Absolutely! Could you have predicted that spectrum could get caught up in a bidding war given its strategic nature? Perhaps! But you did not have any public filing that indicated there was a higher bid out there… in fact, Straight Path’s proxy reveals it was well shopped15 and Verizon was involved in the process before the AT&T deal was announced. This is true benefit of hindsight because the proxy wasn’t filed before the bidding war, but in general I’d suggest things that are well shopped and go to the highest bidder aren’t likely to break into a bidding war, so if you had asked me to guess the odds of a bidding war based on that background I would have said low!

Generic private equity higher prices: It’s not common but certainly not unheard of to read a background and see a company getting sold for, say, $30/share, and that there was a private equity bidder who had offered $33/share and was dismissed for some reason or another. Is that interesting? Sure! But I don’t think that’s close to as interesting as the set ups I’m talking about. What separates them? The MTSR style deals have strategic buyers. That gives them two huge advantages over the private equity bids:

First, a private equity firm generally bids through a fund with committed financing; the moment they walk from a process, their whole deal structure drops…. their committed financing is gone, the deal team moves on, etc. Is it impossible for them to re-engage and spin all of that back up when they read a proxy and see why they were passed over? Absolutely not…. but it’s not easy, and given the proxy generally comes out a month or two after the process ends I don’t think it’s insane to say it’s hard to get the whole gang back together! In contrast, a strategic buyer is generally bidding from their balance sheet / from a bank they have an ongoing financing relationship with, and the whole team is still in place after the first bid fails, so they can quickly get together, read the proxy, and come up with a superior bid if they want to.

Second, private equity buyers have to make everything work on a spreadsheet / from a financial standpoint; obviously you can play games with a spreadsheet to make any math work (just drop the WACC!), but ultimately they do have to sell the thing for more than they buy it to make their fund economics work. Not so for a strategic buyer; they can get very loosy-goosy with their math once they start building in synergies plus maybe the value of keeping an asset out of the hands of a competitor. So you’re just way more likely to have a strategic buyer let their ego and competitive spirits takeover to offer knockouts bids than you are a

Higher bids in the past: every now and then you’ll read a proxy and a company will be getting sold for $10/share, and the proxy will reveal 18 months ago someone had offered $20/share. Again, maybe that’s interesting, but not the set up I’m looking for here. The MTSR set up is so interesting because some strategic was involved in the current process and offered a higher bid. The world changes very quickly; a $20 bid years ago is interesting but doesn’t show a ton about current strategic demand / value.

There are plenty of other interesting situations that I almost put here but I didn’t quite think fit:

in 2021 Kansas City entered a merger with CP at $275/share, took a superior deal from CN a few months later at $325/share, and then dropped that bid for a $300/share bid from CN when regulatory issues arose. Is that a wild set up? Sure… but to my knowledge there was no prior indication of a superior bid before the CN deal came out (and I think the proxy confirms that with benefit of hindsight)!

Another interesting historical one? Back in 2005, VZ and MCI entered a deal for $20.75/share. Qwest stepped in with a superior proposal, leading VZ to bump their bid, and the board went with VZ’s bid despite the Qwest bid being higher due to a variety of factors, including certainty of value and feedback from customers that they’d leave if Qwest bought them (the proxy here is interesting).

Or sometimes the highest bid comes from a sketchy party whose financing sources are unclear, and the board favors a bidder with certain financing over an uncertain one.

Matt Levine had a nice piece detailing board deliberations on anti-trust.

CoStar’s stock was volatile around the bids; the unaffected price value CoreLogic at around $95.76/share, but the proxy reveals the mark to market price was in around $83.73/share.

Disclosure: we have a small MTSR position

This is not the only time the antitrust issues with Novo come up; it’s a concern from the beginning of the sale process. For example, in response to a bid in August, the board communicates “to Party 1 that it would need to significantly improve its proposal and agree to pay a very large termination fee if the transaction was terminated due to the failure to obtain regulatory clearance” (see proxy p. 38)

Matt Levine had a nice piece detailing board deliberations on anti-trust.

As always, I will remind that literally anything can go to zero in the stock market, so I don’t mean that these are literally no lose situations! Go ahead and check out the legal disclaimer to see how much not investing advice this is!

I suppose you could quibble and say there’s some chance a topping bid comes into any deal. Fine, but what I mean here is that, given the proxy background we’re about to discuss, there was a much, much greater chance than normal of a topping bid coming in, and you were paying nothing for it.

Financing concerns could be a reason as well, but you generally don’t have strategics with financing issues. It is possible, but rare. Financing issues generally come up with private equity or financial buyers, and for reasons I’ll discuss later I don’t think they fit cleanly into this type of set up (though they still may be very interesting).

The headline value of the deal was ~$79.88/share, but it included ~$8/share of value from the Vistana disposition that would be completed while the deal was pending / before the bidding war started. For ease of comparing deals, I am excluding that here.

You didn’t even have to wait for the proxy!

I’ll reiterate that human memory is frail; it’s hard to on the spot say “remember this type of situation” and remember all of them. I am happy to be pointed to other examples I’m missing

Even that may be too high. Spirit and Anadarko are really interesting…. but they probably belong in a slightly different bucket as a bidding war broke out almost immediately and you didn’t have a proxy to see all of the background information. MTSR, Fox, and Starwood are my favorite examples simply because the proxy disclosing higher bids was filed and you had multiple weeks to buy after the proxy was filed knowing a higher bid had been out there and see if it came back in. And, again, I also like the set up where the buyer can read the proxy alongside you and specifically target their bid around any concerns the board had / to undercut other bidders.

Novo actually lowered their bid on September 20th from a $56.50 cash bid (with a CVR that could take it to $91) to a $50/share cash bid (with a CVR that could take it to $87), so I will say it’s kind of surprising they could come back with such a big bump…. perhaps some data since the bid was announced made the asset more strategic, perhaps the fact Pfizer bought it got their competitive spirits going, or maybe something else is happening! Either way, with that background, it’s hard to see a wild bidding war breaking out just because everyone seems at the high end of their range!

Well, kind of well shopped. It does seem they were rushing bids and I do wonder if they could have gotten a higher bid if they had let the process play out for another few weeks…. but it’s hard to monday morning quarterback that given they got a massive premium upfront and then got a bidding war that ~doubled the first bid!

The tension betwee Novo's strategic imperative to dominate GLP-1s and antitrust constraints creates exactly the kind of situation where ego and competitive pressure override financial discipline. Their willingness to structure around regulatory concerns with that novel approach shows how badly they want this asset versus letting Pfizer consolidate the next generation pipeline. The proxy background revealing Party 1's higher bid was basically a roadmap for them to come back stronger.

Any else initially think this was about Microstrategy?