A (premium) "no lose" set up

Every investor has an investment set up that just calls to them like a moth to a flame.

Some investors love high and growing dividends (MLPs would be a classic example). Some love founder-led companies attacking a big market (think Netflix, Facebook, or Amazon 10 years ago). Others love levered buyback stories (largely made famous by John Malone and Liberty media, though (as discussed on my book club episode of his recently published memoir, Born to be Wired) the shine has largely come off this model in general and Liberty in particular recently).

I won’t lie; I like all of those set ups to one degree or another. But, for me, there’s a particularly type of investment that is relatively rare but that really gets my heart racing: a bet with no downside (which I have coined a “no lose” bet1). These are bets where you only have two outcomes: you make money, or you roughly breakeven. There is no chance of a loss (I say this with the caveat that anything can lose money at any time, so I don’t mean there is literally no chance of a lose and this is certainly not investment advice; I just mean the chance of loss is so rare that it would take something truly strange happening to lose money); in other words, “Nothing bad can happen; it can only good happen2.”

These types of bets are relatively rare; they most frequently happen in two situations:

Pre-deal SPACs trading around or below trust: these are fantastic set ups. If the pre-deal SPAC announces a buzzy deal, the stock can really take off. If the SPAC fails to announce a deal or announces a deal that fizzles, then you can redeem the SPAC and get your cash (plus interest!) back. There’s no real way to lose short of the SPAC running some type of shenanigans with their trust (which has happened before, but it is exceedingly rare3).

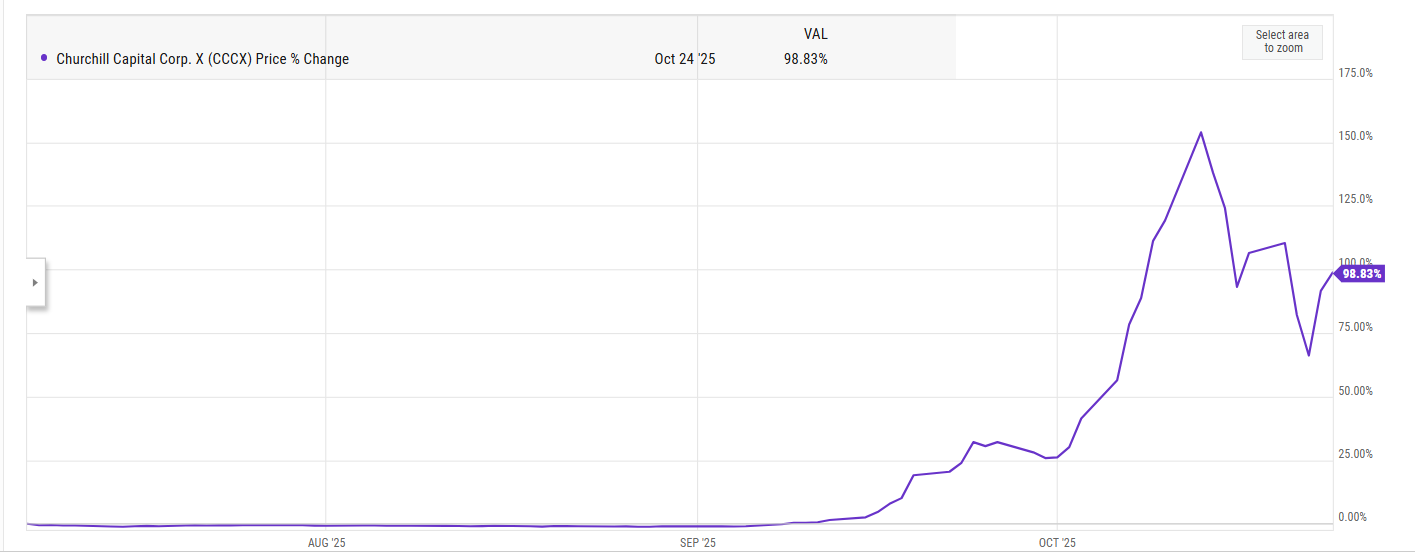

Pre-deal SPACs have been off and on a huge focus for me over the years (we even run dedicated Pre-Deal SPAC separate accounts; we’re always happy to chat SPACs if you’re interested in that strategy), including earlier this year with my pre-deal (premium) SPAC basket. That post mentioned 6 SPACs (3 focus ones and 3 honorable mentions); one of the honorable mentions (CCCX) nicely illustrates the risk adjusted nature of pre-deal SPACs. It announced a buzzy deal, and the stock has doubled in less than four months4. Not bad for a SPAC that was trading at trust!

Merger arbitrage with the potential for an interloper to come in with a higher bid: The set up here is equally simple: a company announces a deal to get bought for $10/share, the stock trades for a normal arb discount (say, $9.80/share), and you think there’s a chance a higher bid comes in. Generally, a higher bid possibility would happen in a company whose deal has a “go-shop”, but there are certainly plenty of examples of companies who announced a merger agreement without a go-shop getting a bump (for example, Disney’s initial deal to buy Fox did not have a go-shop; that didn’t stop Comcast from entering with a higher bid and kicking off a bidding war!). Again, it’s a “no lose” set up: if a higher bid comes in, you make a profit (often a large one; Disney took their offer from $28/share to $38/share after Comcast kicked off a bidding war), and if a higher bid doesn’t come in you’ll ~breakeven since the original merger is still on. The only way to lose is for the merger to break; obviously mergers can and do break (and they break much more often than SPACs run into trust shenanigans), but it is still rare enough that we can loosely define this as a “no lose” set up.

The issue with both set ups is they are reasonably rare. It’s not that there aren’t plenty of SPACs and merger arbitrages; there are literally dozens (or hundreds!) of both every year. But there are only a handful of SPACs a year that announce deals that result in any type of pop5 (to say nothing of a CCCX style doubling!), and the historical success rate for go-shops is around 5% (and the odds of a bidding war on a deal without a go-shop are even lower!).

So, to me, the key is to be selective and find SPACs / merger deals with some type of uniqueness that indicates it’s more likely than a typical deal to get a pop / overbid. With SPACs, that’s often finding sponsors with some unique ties to buzzy companies or industries (if Kimbal Musk ever sponsors a SPAC, I’d be all in at trust value!). With go-shops or bidding wars, that’s generally identifying companies that entered into a deal with some type of flawed process or perhaps under duress that may have precluded them from running a process that could fully flush out their value6.

Why do I mention all of that?

Well, the market is pretty frothy in certain sectors right now, and I think that presents opportunities on the SPAC side. I really like my current SPAC basket, but given the number of interesting SPACs and angles out there I’ll likely be adding a new SPAC basket in the near future.

But I’m writing this particular article because there is one current M&A deal that I think has particularly good odds of an overbid: