mNAV premiums, market multiples, and relative value (weekend thoughts)

I’ve mentioned a few times that the market feels kind of manic and expensive to me right now. Does that mean we’re on the precipice of some imminent collapse? No, of course not. Does that mean stocks can’t go up from here? Again, of course not…. but it does seem to me that if you’ve got a decently long time horizon, equity returns will be lower than they have been over the past 10-20 years. I don’t think there’s anything crazy shocking in that statement; the S&P has done >10% annualized over the past 20 years, which is well, well above long term equity returns.

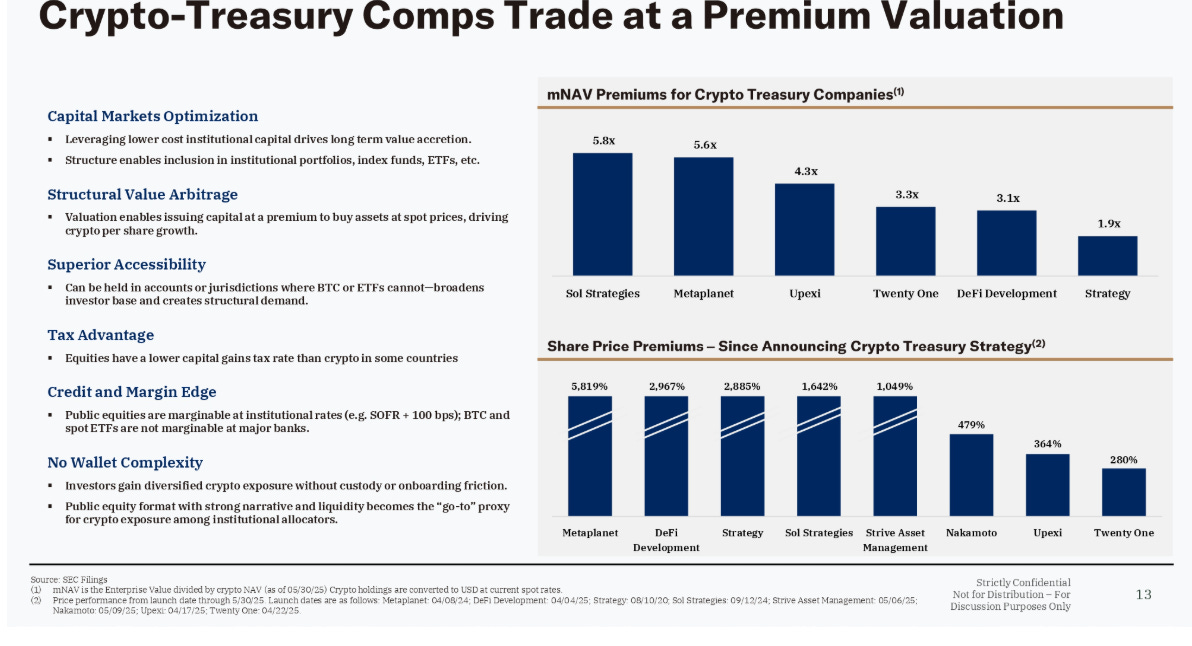

Anyway, right now the markets are euphoric, and crypto-treasury companies in particular are all the rage. If you’ve been living under a rock, a crypto-treasury company is a company that buys bitcoin (or some other crypto) and HODLs it on their balance sheet. For some reason, the market has decided these companies should trade for a huge premium to NAV. This slide from MBAV’s1 deSPAC presentation illustrates it well:

The thing with crypto-treasury companies is they are like catnip for relative value arbitrage2. Say you’ve got two crypto-treasury companies that are both focused on bitcoin. One trades for 4x NAV, and the other for 2x NAV. That creates all sorts of interesting theoretical hedging and arbitrage opportunities. You could:

Buy the cheaper crypto-treasury at 2x NAV and short the more expensive one at 4x NAV and profit from the spread collapsing3.

Short both of them at a premium to NAV and buy bitcoin (or whatever crypto they are HODL’ing; I say bitcoin because it’s the overwhelmingly dominant crypto-treasury asset), betting that the multiple on both will compress closer to 1x NAV

Or you could reverse that trade: if you think they should trade for bigger premiums, you could short bitcoin and go long both the treasury companies!

Those are simple trades4, but I’m sure you could dream up dozens of other relative value trades, particularly once you start to introduce options and other, indirect plays on bitcoin into the mix!

But I wanted to focus on the first one: I personally think it’s crazy that crypto-treasury companies trade for a premium to NAV. Let’s assume you do too, not because it’s important that you do (everyone can believe anything they want!), but because it helps with this hypothetical. If you and I both believe crypto-treasuries shouldn’t trade for premiums, then I would never come to you with a long pitch and say “this company is cheap because it trades at 2x NAV and every other crypto-treasury company trades for 4x.” I might come to you with a relative value long/short trade like the one I discussed above, but I’d never come to you with an outright long case.

I’ve been thinking a little about that example as it relates to stocks. I’d never pitch you a crypto-treasury company trading at a premium to NAV even if it was at a discount to other crypto-treasuries…. but I might pitch you a restaurant trading at 8x earnings if all its peers were at 12x, or a random company trading at 12x earnings if the market overall was trading at 20x. And, in each case, a big piece of my argument would be “this company trades at a discount to peers / the market,” and you’d probably nod along and think “that’s reasonable! pretty big discount; worth doing some work on!”

But is that thinking reasonable?

Why should that thinking be reasonable for stocks, but not reasonable for crypto treasury companies?

The answer might very well be, “it’s not reasonable! You’re short handing a relval trade but leaving yourself exposed by not doing short leg of the more expensive side (in the same way you’d be leaving yourself exposed if you bought a crypto-miner at a premium to mNAV and didn’t short a more expensive one).”

Or the answer might be, “you’re comparing trading at a premium to asset value to earnings multiples / yields; that’s kind of apples to oranges!”

I could agree with either.

But it’s an interesting line of thinking, and I think it kind of underlines some of my hesitancy with the general market recently.

When the market keeps running and valuations get stretched, it’s really easy to find things that are cheap on a relative value basis. I could point you to 100 stocks trading for a discount to the market in half a second with a screener or something.

But as multiples race, even the things that are trading cheap to the market get more and more expensive, and often that leaves you exposed in weird ways.

Consider this: say there’s been a huge market run up, and you see a legacy media company that’s now trading for 8x P/E while peers are trading for 16x and the market is trading at 30x.

You might be thinking “now that’s a great relative long”…. but what if I told you a year ago the legacy media company was trading for 5x P/E while peers were at 12x and the market was at 20x. The legacy media company would actually have further to fall if everything reverted back to their year ago multiples than the peers and market5!

Again, none of this is fair. These are really simplified examples; the market is a much more competitive place than just sorting by P/E and saying this is expensive or this one has further to fall if it trades back to the multiple it traded for last year.

But I think they nicely illustrate some of the dangers of a rising market and some of my worries about what I’m looking at / why I’m finding it a little harder to find value right now: when the market races, it’s tempting to buy the cheapest stuff you see and think you’re practicing value investing, but the cheapest stuff can (paradoxically) be the most expensive / have the furthest to fall if the market turns.

Disclosure: I am long MBAV in very small size as part of my SPAC basket

Humorously, as I was writing this, my book club cohost Byrne Hobert published you’re always betting on relative value. We are talking about two completely different forms of relative value…. but I really enjoyed the piece and in some ways it’s an interesting companion piece to this one.

Obviously none of this is investing advice, shorting is super risky, see our legal disclaimers, etc.

At least they’re simple in theory; in practice they are insanely difficult given margin requirements + the potential for the side that trades rich to squeeze / go to an even crazier multiple!

In this case, the legacy media company would drop ~37.5% (from 8x earnings to 5x) while the peers would drop 25% and the market would drop ~33.53.