Evolving, improving, and #friendship (part 2)

Tl;dr: This is part two (you can find part one here!) in my series building on my podcast (#333; Perfecting the investing craft with Caro-Kann’s Artem Fokin) and Alphasense webinar (on using expert calls and AI) with my good friend Artem Fokin. I really enjoyed the podcast (and it’s gotten very strong reviews; I had several people text me they thought it was the best podcast I’ve done), and I think you will enjoy it too…. but I also wanted to build off some points / thoughts from the pod.

In part one of this series, I used a sports metaphor to show the importance of improving / evolving as an investor and talked about why my writing / thinking about process has increased this year, including my fear of getting left behind if you don’t evolve / improve. I’d encourage you to read that post for background here; assuming you’ve done that, let’s turn to one of the other reasons I’ve been so interested in process improvement recently: opportunity in the inflection.

A lot of investors describe themselves as “inflection investors.” It’s a really great way to describe a strategy: wait for something to inflect positively (or negatively), and then buy it (or short it!) and, when the inflection drives huge positive growth, the market will be forced to rapidly rerate the company.

It sounds so simple in theory! In practice, I’ve found “inflection investing” requires a lot of deep work and specialized industry knowledge… but, more than that, I’ve found that inflection investing means a lot of different things to different people.

For example, I find inflection investing is most commonly used by macro investors. And what they’re commonly describing is investing in some type of commodity when supply is constrained and demand is just starting to outstrip supply. That’s the type of inflection that can result in a quick squeeze / send prices parabolic1.

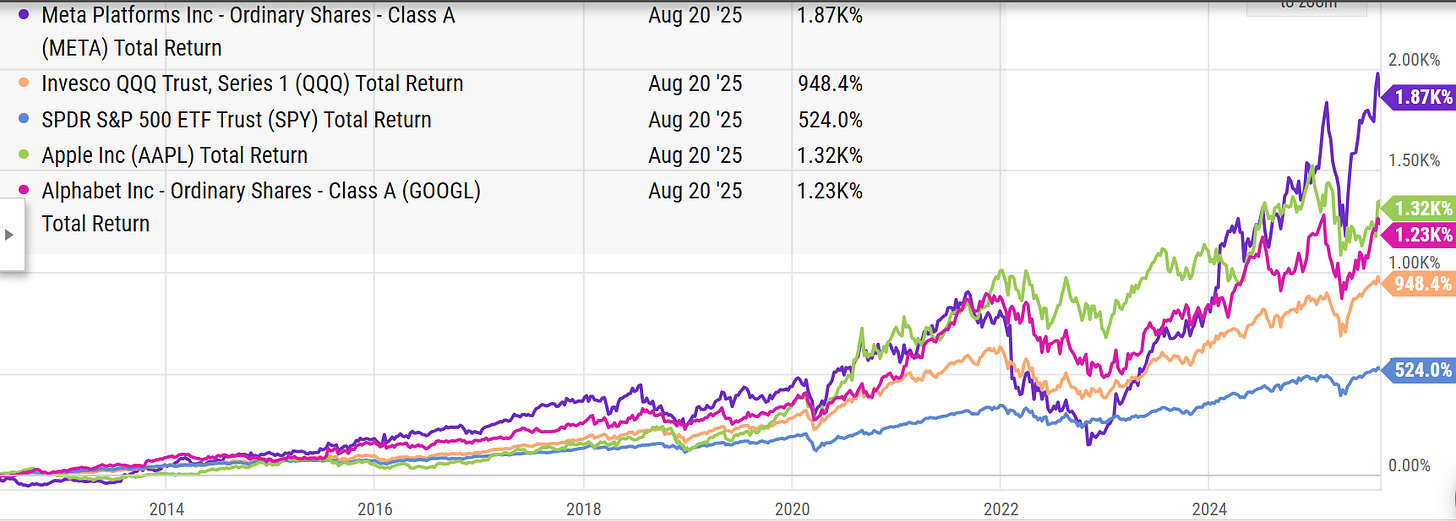

But you could use inflection investing to describe a lot of things. It actually fits really well with thematic investing / paradigm shifts. For example, consider mobile and think back to 2012. Facebook announced a deal to buy Instagram on April 9, and then IPO’d in May. I’m not saying this to say “you should have bought the facebook IPO”; I’m pointing this out because at that point it was clear that mobile was the future…. if you had that one insight and simply said “let me buy the companies that make mobile phones”, you had successfully identified an inflect. You could have bought Google or Apple and you’d have 12-13x’d your money over the next ~13 years (to today), smashing any relevant index.

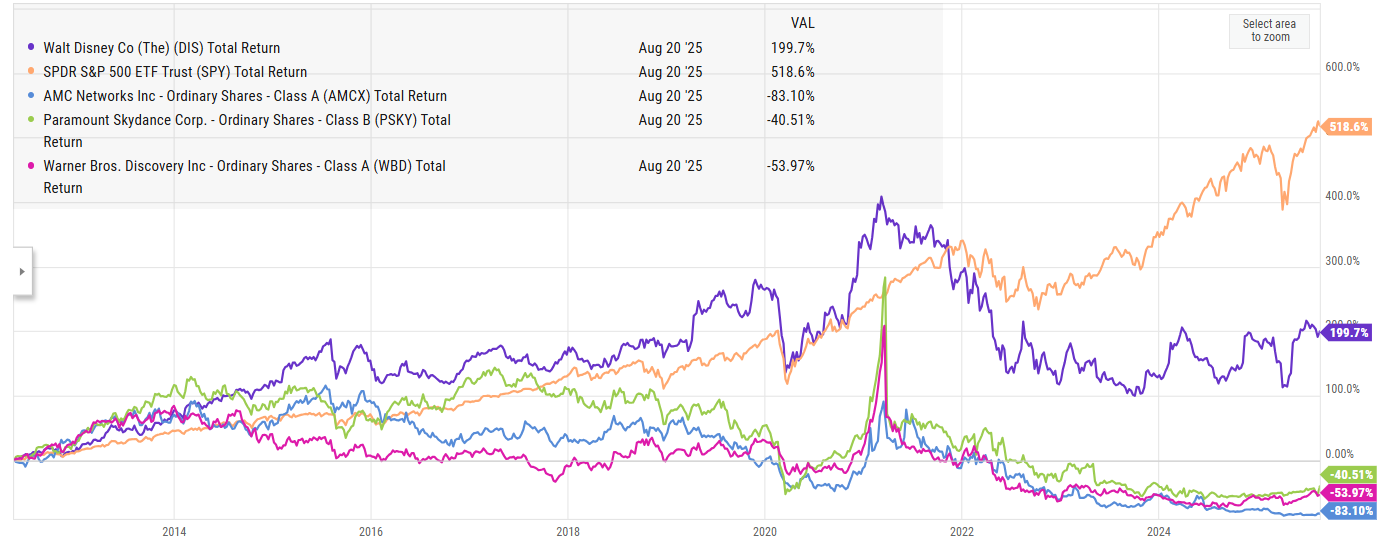

Alongside the “buy mobile phones” insight, you probably could have identified a few businesses that would be really harmed by the spread of the internet; legacy cable media (like CBS) in particular comes to mind2 (though there of course plenty of other losers!). If you had that single insight, you had the making of a great multi-year short as all of the legacy media companies substantially underperformed the index over the next 10+ years.

I’m not here saying those insights are easy to arrive at, or that there are guaranteed winners or losers in any paradigm shift (you may have thought the shift to mobile would devastate legacy Facebook, or that the rise of the internet and mobile be devastating to Netflix given its legacy DVD model…. both would have been poor insights to monetize!). What I am saying is that paradigm shifts create multi-year winners and losers that you can monetize with the correct insight.

The AI shift is here, and with it will come multi-year winners and losers. That’s probably pretty obvious (and probably right; there’s always a chance the AI bubble is similar to the dotcom bubble or fiber internet overbuild!)… so there’s some thematic winners and losers you could surely find if you’re smart enough (though it’s not easy!).

But that’s actually not the type of inflection I wanted to talk about.

The inflection I wanted to talk about is the inflection that happens when new ways to research get released. When that happens, there’s often big potential alpha for early adopters.

Let me give a sports example to show where I’m going. The NBA introduced the 3-point field goal in 1979-1980. I mentioned this in part 1, but in the early 80s entire NBA teams were taking less 3 point attempts than star players do today. It took a long time for NBA teams to adopt proper strategy along the three point line; if you were a team willing to push the three point line and adopt it early, you had a huge mathematical edge.

Similarly, think back to the early days of investing. Ben Graham and Walter Schloss made great returns literally by being bean counters: they’d pull up a balance sheet, subtract the liabilities from the assets, and then buy the stock if it was trading cheaper than that asset value (or some percentage of that)…. but, in the 70s and 80s, computers started to get more widespread. If you had some mathematical talent, you could be an early adopter of computers and use simple statistical models to eat everyone’s lunch… and, if you kept pushing, that early lead could keep you at the forefront of quant investing and you could build a sustainable business (I’m basically describing how Renaissance got founded, though obviously having some PHDs in there helps!).

Today, AI is clearly on the rise in all fields; I think it will clearly materially change the investment research process, and that potential change creates really interesting opportunities for individual investors to generate a lot of alpha.

No, I’m not saying that if you’re an individual investor there’s an opportunity to go build an AI tool on your own that will create the next great quant firm. I suspect the large quant firms have huge edge on that.

But I am saying that the rise of AI will create a different reward structure around different skills, and individual investors who are early to figure out which skills get rewarded in an AI world can make a fortune. Let me again give a sports hypothetical, then give some historical market examples, and then give some suggestions.

Let’s turn back to basketball. As the three point shot has taken off, the game has become much more stretched out (you need to defend out to the three point line and beyond versus only at the basket). Thus, the returns to being quick (so you can cover more ground) has increased, as have the returns to being a good shooter (more three point shooting = more returns for being a good shooter). The returns for being simply big and bruising have gone down as the game has stretched out (a slow, brooding big man who couldn’t shoot used to be a very valuable player; as the three point line has taken off, that player archetype has largely disappeared).

In investing, if you were really good at math, you could make really good returns before computers came along just by… doing math (the Graham/ Schloss example mentioned earlier). Those returns got arbitraged away as computers took off (though maybe if you were really good at math you could do the computer programming)…. but, as that got arbitraged away, the returns for some other types of thinking went up. For example, I’d suggest the returns to creativity have gone up as computers have proliferated. I’ll give you two broad strokes as examples, though you could imagine plenty of others:

Thematic investing: If you think of great themes from the early 20th century, you’d have been buying very cyclical and asset heavy companies (steel, railroads, autos)…. maybe you could have profited, but that’s a tough game! In the early 21st century, identifying themes like “mobile” or “search” would have led you to investing in some of the best businesses the world has ever known!

Creative data usage: In the 60s, Warren Buffett famously got comfy investing in Amex in part by asking restaurants how their diners were paying. That was creative… but it was a very small sample size and pretty unscientific. But fast forward to the present: in the 90s and 2000s, satellite imagery and credit card data started to proliferate. If you were really creative, you could have been the first person to think “what if I use satellites to track how full parking lots are” or “what if I buy some credit card data to see how sales are going intra-quarter”?

So my challenge would be this: AI is clearly going to change a lot about investing…. what skills is it going to reward? What new ways of investing is it going to encourage?

I obviously don’t know the answer (though I have some suspicions)…. but if you’re an talented / hungry investor and you can identify some skill set or data set that is really enhanced by AI, there’s a very good chance you could find a multi-year edge that let’s you generate substantial alpha.

Let me loop all the way back: the whole purpose of this series was to encourage you to listen to my podcast and webinar with Artem. What does everything I’ve mentioned in these posts, including the NBA’s evolution as it adopted the three point line and satellite tracking of parking lots, have to do with the podcast / webinar?

Well, everything! We ended up covering a lot of different things on the podcast, but the core focus was working on yourself and improving as an investor. And the core focus of the webinar was discussing AI and expert call networks, the two tools that have most materially changed / improved the research process for fundamental investors in the past ten years (at least IMO!).

So, yes, I am biased…. but at lot of thought and effort went in those podcast / webinars, and I think they’re fundamentally an excellent product. If you haven’t yet, I’d encourage you to check them out…. given you’re a reader of this blog, I’d just be absolutely shocked if you didn’t enjoy them!

PS- this post was called Evolving, improving, and #friendship. We’ve talked about the first two so far, but I’ll just briefly mention the third: obviously Artem’s a friend, and I find the “evolving” and “improving” pieces are much easier (and more fun) when you’ve got a friend to help you do them. That’s what talking to Artem does for me, and I’m sure you’ll see it in the podcast / webiner!

I openly acknowledge this is a simplification, and you could paint plenty of other types of inflections. But I think it serves as a nifty example.

Why? The continued rise of the internet and mobile lowered the distribution cost of video, destroying the best barrier / moat for media companies.