Weekend thoughts: net cash in a rising rate world (follow up)

I got a lot of interesting feedback / pushback on yesterday’s “Weekend thoughts: net cash in a rising rate world”, so I wanted to provide some quick follow up.

Let me start with the most obvious: a lot of the pushback came from me using BLDE as my example of an over-cashed company. That was an error on my part; I wanted to use a company that had more net cash than market cap, and for some reason BLDE was just the first one that came to mind.

Why the pushback on BLDE? Because BLDE is burning money like crazy as they try to scale he business, and multiple people pointed out that there is value in having a cash runway for company’s that are trying to build themselves up into a real business.

I agree with that pushback…. to a point.

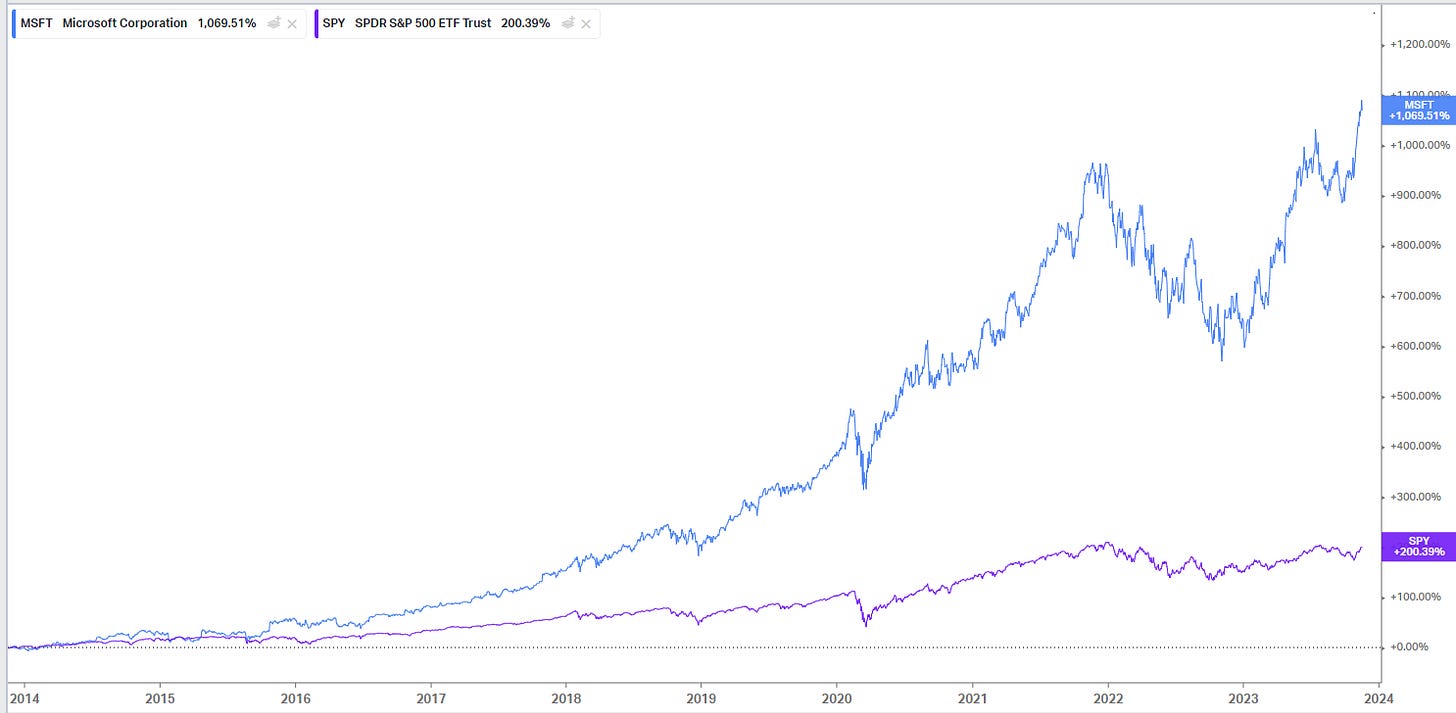

So let me start with what would have been a better example: Microsoft. As of last quarter, Microsoft had $143B in cash + short term investments versus maybe $70B of debt. In FY23, MSFT did ~$60B in free cash flow to equity. Microsoft is a moat-y business that gushes off cash (mainly through subscriptions!) and is reasonably economically resilient; it is just wildly ineffecient for them to sit on a cash balance greater than one year’s free cash flow. MSFT is the type business that is begging for some leverage; I think a reasonable ~1x net leverage policy would leave MSFT super investment grade rated and create much better returns for their investors.

I’ll see a lot of people say, “MSFT is a huge beneficiary of rates going up; now that >$100B cash pile can really earn some interest!” And I just think that’s wrong; as mentioned in yesterday’s post, the huge cash balance is inefficient from a tax perspective and it drags down the return on the stock. Shareholders would be much better served having that excess cash in their pocket so that they could invest purely in MSFT’s business when they buy the stock.

Now, given the historical returns on the stock, I’m sure MSFT’s shareholders aren’t super concerned with a little headwind presented from holding on to too much cash…..

But I think that’s very “the stock has gone up so everything worked out” / results driven thinking. For one, MSFT’s shareholders clearly would have been better served if the company had taken all that extra cash and bought back stock (or even just dividended it out so the stock could compound at the rate the business was growing at and not get hit with a cash drag). Of course, that thinking also presupposed that Microsoft’s stock was a winner, and that was no sure thing 10 years ago. Remember, 10 years ago Microsoft couldn’t get out of their own way and was in the process of a disastrous Nokia acquisition. So yes, using all the excess cash to buy back shares might not have worked out in those alternate worlds…. But I’d actually argue the world we live in is the world where MSFT’s cash balance looks the best. Imagine if Microsoft had continued to bungle along. That huge cash balance would have served as a prop to entrench management; it could have kept them in charge of a business that continued to make strategic missteps and prevented activists from coming in / changing up the management and strategy when necessary. Or it would have been used by management to fund even more disastrous acquisitions that destroyed even more shareholder value.

To me, the bottom line is a huge cash balance is super inefficient, and for businesses that are generating cash, on the whole shareholders would be better of if all excess cash was returned to them instead of sitting on corporation’s balance sheet and tempting the management team to do something with it.

A reader commented on another great example of corporation’s “investing” their assets in silly ways that create drags for shareholders: Palantir bought ~$51m of gold bars a few years ago. Per their 10-Q, they sold the gold for roughly break even this year.

Was buying gold bars in 2021 a good idea? Maybe! Again, I’m not here to judge on results alone. But buying gold inside of a corporate structure is a terrible idea for a company! There’s no business reason to do it, and shareholders would be better served having that cash in their pocket and getting to buy the gold themselves if they wanted to!

Similar thinking would apply to publicly traded companies that take their excess cash and invest it in all sorts of other financial assets (real estate, bitcoin, stocks). Unless you are a financial company whose purpose is explicitly to buy financial assets (and you have the corresponding financial, legal, and corporate structure to do so), your shareholders would generally be better served if you returned the excess cash to them in some way (either dividends or repurchases) and let them worry about investing cash while you (as a company management) focus on running your business and maximizing its value.

Ok, so that covers some better examples of the “having cash creates a drag on shareholder returns.” Let’s turn to the other pushback I got: that cash burning businesses, like BLDE, have some benefit from having excess cash to invest in their business as they try to scale.

I certainly agree with that take; however, there is such a thing as too much cash! To illustrate, let’s consider a pharma company with one asset: a phase 1 drug. Obviously, this company needs a bunch of cash to fund trials and get to approval…. but there is such a thing as too much cash. To get approval, a drug generally needs to go through a series of increasingly expensive trials (phase 1 trials have a handful of patients to test safety and efficacy, phase 2 goes a little broader to start getting better data, and phase 3 trials will have hundreds of patients to get robust and statistically significant data). Let’s say it would take $10m to fund a phase 1 trial, $30m to fund phase 2, and $60m to fund phase 3. So, all in, getting the drug to approval would cost ~$100m.

What’s the right amount of cash for that company?

It’s clearly not “$0”. That company can’t be dependent on the capital markets every day to fund their trial / research. They need enough cash to give them line of sight into hitting the next stage of the trial.

However, the right answer cash balance answer also probably isn’t $100m, which would fully fund all three phases of the trial and get them to approval. That’s not the right answer for three reason:

First, there’s always the chance that the drug fails. If the drug failed after the first phase, suddenly you’d have a company with $90m in cash and no viable pipeline assets, and you’d likely be in that “corporate governance trading at a discount to cash” issue I mentioned in the first post.

Second, raising $100m upfront is inefficient. If your phase 1 trial succeeds, you should be able to raise money on much better terms to fund your phase 2 trial (i.e. if the drug has blockbuster potential, you could probably raise $10m at a $20m valuation before your phase 1 trial, and then if it’s successful it wouldn’t be crazy if you could raise $30m at a $300m valuation for your phase 2 trial).

Third (and somewhat related to the first two), the need to raise cash does serve as a self-correcting mechanism. If the phase 1 trial succeeds but the results are really disappointing, or the market changes so that the drug’s market place isn’t the same as projected (maybe a new, way superior drug gets approved between the phase 1 trial starting and concluding, so that your drug is now no longer needed), needing to go out and raise every now and again can serve as a proof point that the drug is still viable desirable to fund.

So the right answer is probably something like $25m in cash; enough to cover the phase 1 trial (plus any possible overages) and get started on the phase 2 trial (once you have proof of concept from phase 1) before needing cash.

Single drug pharma companies are a unique example, but honestly the same applies to a business that needs to burn some cash before hitting scale. Let’s say your business has a plan that would take 5 years worth of cash burn before hitting break even. It’d be quite inefficient to have all five years of cash burn sitting in a bank account; better to have ~2 years, and then go out and raise more cash in a year as the business model proves out (and to check that the business you are building is still viable / fundable).

A lot of the more recent VC blow ups (think WeWork) would have actually been bettered served by similar logic; yes, the market (and by the market, I mean Softbank) was probably so wild that they would have gotten funded anyway, but if they weren’t raising so much cash at such wild valuations and instead had only been raising enough to fund a year or two of operations at a time, the market may have been able to run a check on their business models and forced them to reset / slow down before they signed so many wild leases that bankruptcy was an inevitability.

This is an interesting topic. Here's maybe a tad of perspective (not a prediction!) that you may find of interest. When I started on Wall Street in 1980, there were many companies with sizeable cash balances and nearly debt-free balance sheets (or only mortgage debt on owned properties). Why so conservative? A few reasons. 1) many companies were run by CEOs who had survived the Great Depression only because they were not debtors. They knew nobody was going to bail them out (for decades, the same was true of banks - not in the last two or three decades). Factor in a terrible downturn from 74-75, and then Volcker jamming rates to the moon in '81 - a period of immense challenge for most public companies - and that concern was only enhanced. 2) Hostile takeovers (and greenmail) were unheard of as no major investment bank was willing to go hostile. Only after the rise of a few mavericks (and Mike Milken at Drexel) were hostile actors able to get the financing they needed to be a real threat. In today's world a non-controlled company that keeps way too much cash will eventually attract an activist who tries to get the cash sent back or used up. 3) Stock buybacks were illegal throughout the 60s and 70s unless you made a tender offer to all shareholders (as Henry Singleton did when his stock got super cheap after he had used it as a super expensive currency to acquire 50 or so companies). And management was not generally incentivized with stock, so there was no imperative to "enhance shareholder value."

It has been a long time since an economic downturn with the magnitude of the Great Depression or the 73-75 debacle which was shortly followed by Volcker and his 20% interest rates. Given all of the other incentives to "optimize" cash, it's entirely possible that the next persistent downturn (whenever it occurs) will result in outsize #s of bankruptcies and loss of equity value as companies that could have maintained a financial cushion to pay down debt or see through a period of operating loss gave up that flexibility to the altar of stock buybacks and enhancing shareholder value.

One of the most interesting aspects of financial history to me is trying to understand the mechanisms of how markets get super cheap and super expensive relative to normalized valuations. And it seems that in recent years, many have internally accepted premium valuations as "normal." We may be about to find out if that belief has been misplaced.

I saw many quite suprised that ROIV didn't rally after the Roche drug acquisition annoucement. Yet another example of (soon to be) too much cash on the balance sheet. One could also say the same thing about BUR and the YPF news. Though yet to be collected, a windfall is all but guarenteed. In Burfords case the stock popped for a short period of time and settled back to where ot traded pre-YPF win. I guess having a crystal clear capital allocation framework is important. I'm not sure what the lesson is but interesting to think about