Tegus Sponsored Deep Dive #6: The Offshore Inflection, Part #3

Welcome to part #3 of my Tegus sponsored deep dive into the offshore space. You can find part #1 of the deep dive here (I’ll refer you to that post for more background on why I’m interested in the space, the aims for the deep dive, etc.) and part #2 (discussing two of the bull points) here. This post is part the sixth entry in my deep dives sponsored by Tegus series, where every other month Tegus gives me a few expert interviews to dive into an industry (with the hope the resulting posts drive publicity to Tegus / shows how the platform can be used to get up to speed on fundamental investments. So please check out Tegus if you haven’t done so already!)

The bull thesis for the offshore market has three points; we covered bull thesis point #1 (days rates are set to keep rising) in part 1 and part 2 covered bull point #2 (no looming supply or demand response to rising rates / tight utilization) and point #3 (even without continued rising rates, offshore is cheap on current earnings / rates). In today’s post, I’m going to wrap the series up by discussing the bear thesis and some other lingering thoughts I didn’t quite have space to include in the first parts.

Let’s dive right into the bear thesis.

Offshore bear thesis

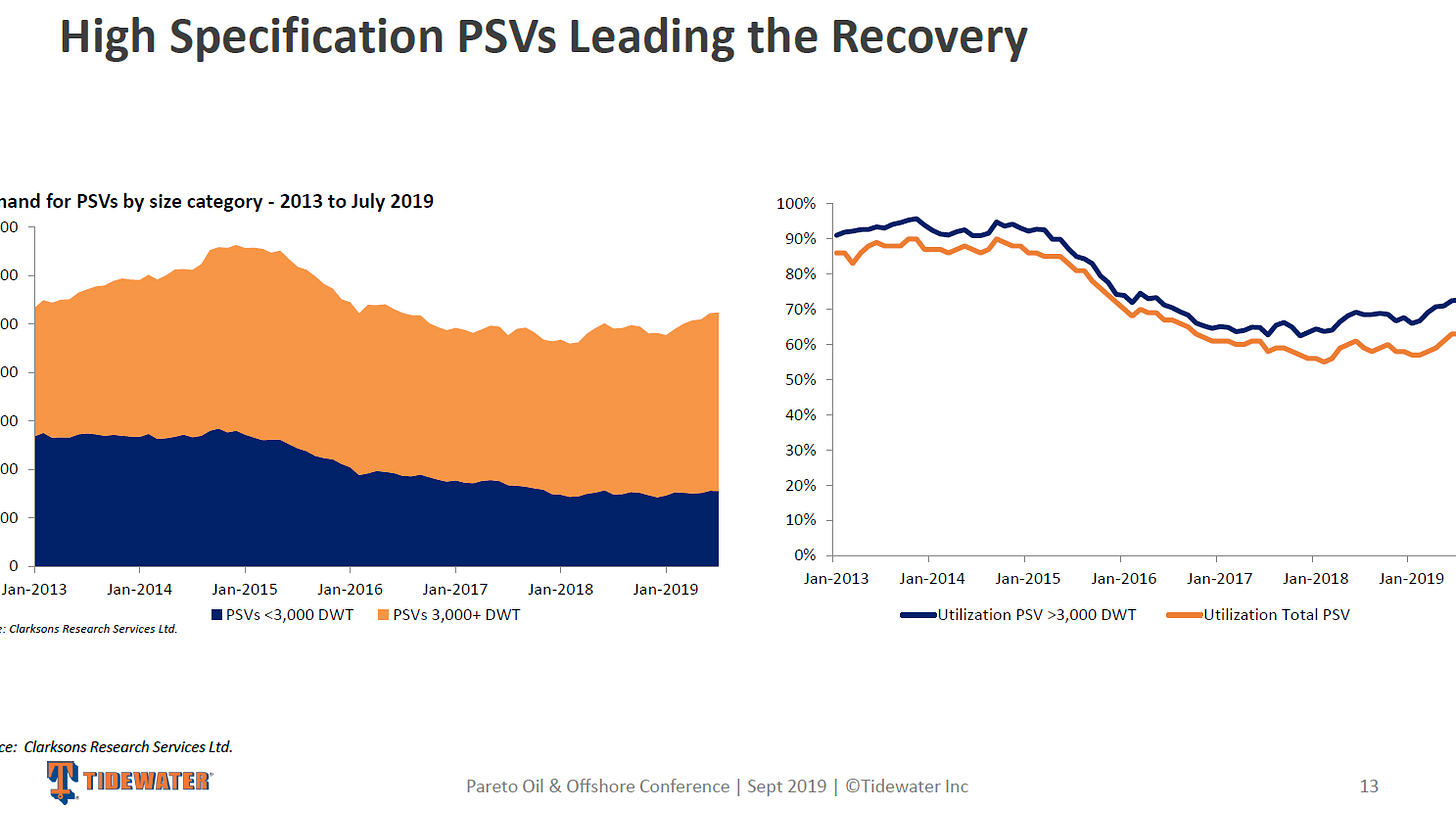

If I had to sum up the bear thesis with one slide, it would be with the Tidewater slide below.

Now, you’re probably thinking “um, that slide discusses how the supply dynamics are improving. Isn’t that exactly the bull thesis you were hammering in parts #1 and #2?”

The answer to that question is yes!!!!

But look at the date on that Tidewater slide. September 2019. Six months later, COVID would hit, oil prices would go negative, and half the industry would file for bankruptcy (and the only reason the other half didn’t file is because they had already gone bankrupt a few years prior!).

The unfortunate reality is that the industry always thinks the supply/demand dynamics are improving. Always. I’ve reviewed ~12 years of investor decks for the industry, and I can find near infinite amounts of slides that say either “fundamentals are improving!” or “fundamentals are weak but will quickly get better due to looming supply issues and demand growth.” The most negative things I can find the industry ever saying is at the absolute nadir of a cycle companies will say something like “things are awful but we can survive and things will quickly improve after our peers fold." So I can find plenty of bullish statements…. but I can’t find a single slide that says “fundamentals are good but demand is about to drop and we’re going to have way too much supply.”

I think I can show this best by showing the evolution of Transocean’s (RIG) investor slides from 2013-2016. Remember, Transocean is basically the only offshore player that didn’t go bankrupt over the past 10 years. This exercise of going through the past decade of investor decks for the industry was made difficult because most of the industry has gone bankrupt, and in general the post-reorg companies have wiped any presentations they had pre-bankruptcy from their investor sites. Fortunately, Transocean’s old decks remain on their website in all their bullish glory.

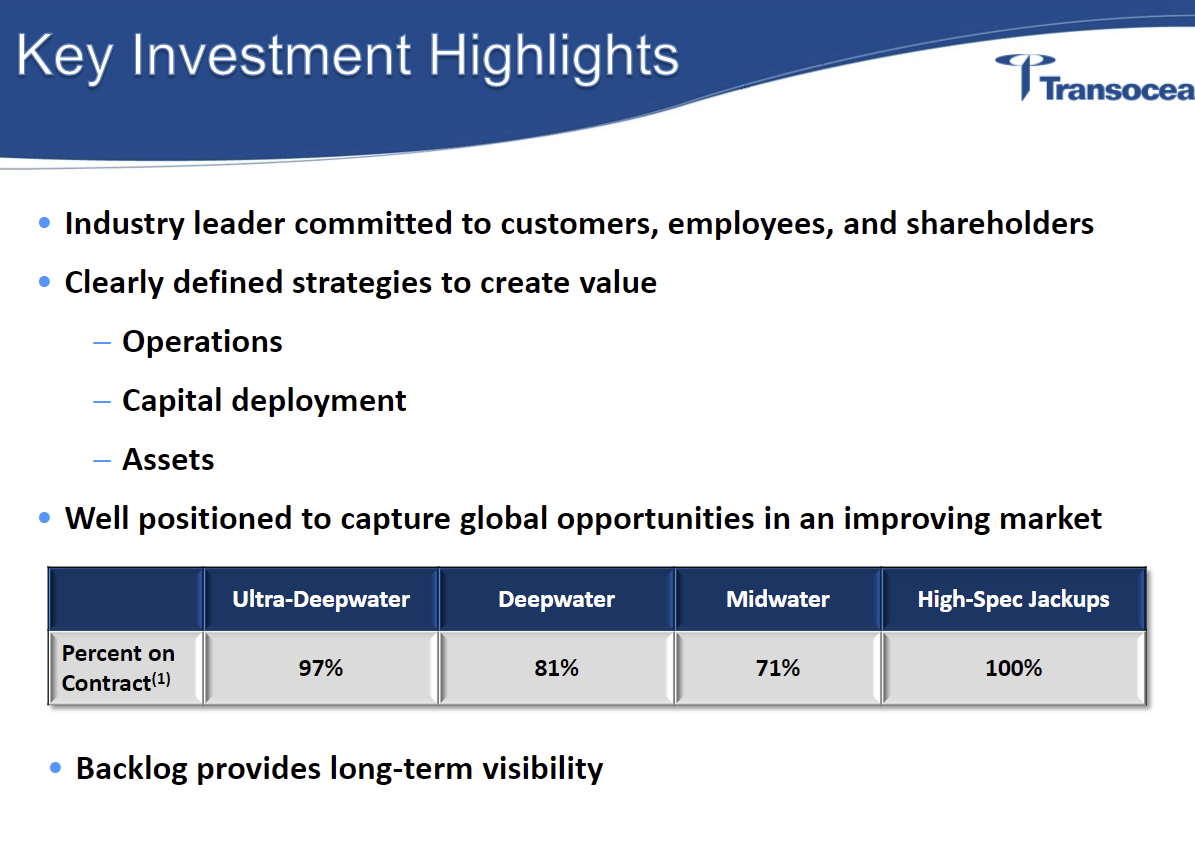

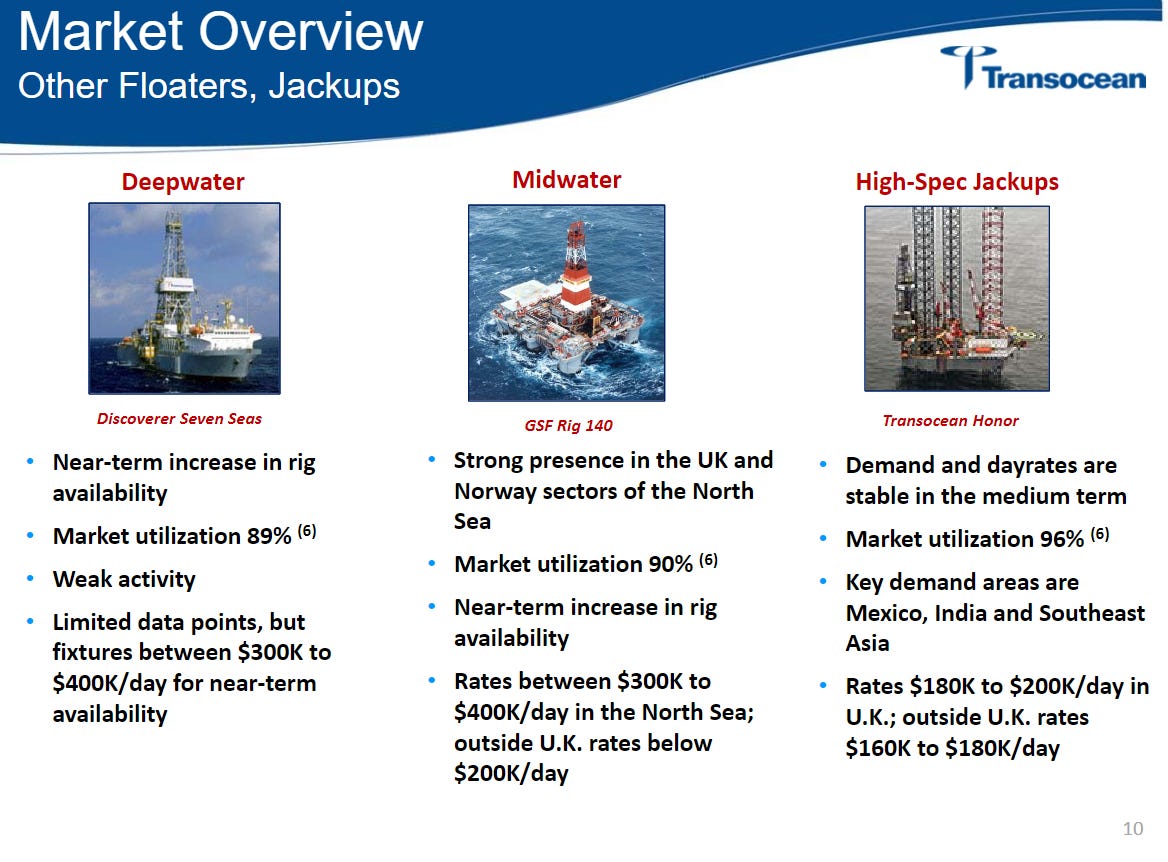

Let’s start this trip down memory lane off with two slides from RIG in early 2013 (at a CS conference). Note they’re focused on “global opportunities in an improving market” and discussing how tight global utilization is leading to pretty wild rate (~100% ultra-deepwater utilization leading to rates at $600k+). Seems like a good time to invest, no? (PS- just to be clear, RIG is not on outlier in terms of the bullish pitch. Here’s a DO presentation from around the same time that is just as bullish).

Fast forward just a few months to RIG’s November 2013 investor day. Suddenly, and RIG’s talking about challenges in the near term market…

Jump forward in time a little further and in August 2014 RIG says the market is “weak” due to oversupply. Where did that come from? Just a year earlier we were talking about skyrocketing day rates and 100% utilization!!

That’s a pretty wild swing in just ~18 months…. and it would get worse! By early 2016, RIG is just flat out complaining that the price of oil doesn’t make any sense and providing investors a liquidity analysis to show they won’t go bankrupt!

Put together, the evolution of those slides illustrate the most frequent pushback I get on the bull thesis (and the thing I worry about most): the industry always says that the next bull market is right around the corner.

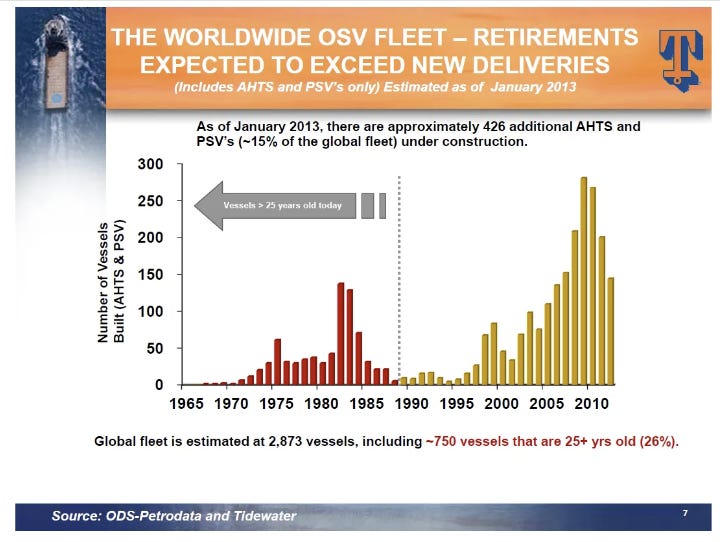

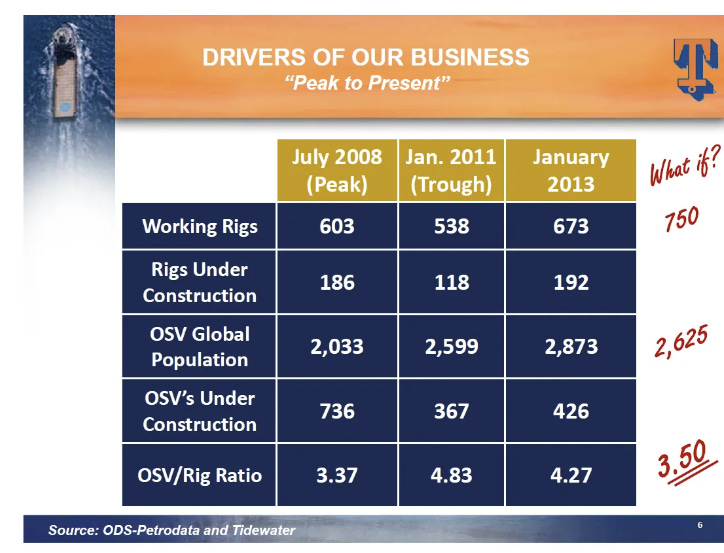

I don’t want to beat you over the head with this idea, but I did start the series off with two Tidewater focused podcasts (episode #146 (with Tidewater’s management) and episode #147 (with Judd Arnold)), so I just want to show a few slides from Tidewater’s past to illustrate this point a little further and drill into it. The slides below are from a TDW 2013 investor deck.

They say history doesn’t repeat, it rhymes….. but whoever said that clearly hasn’t studied the shipping industry. The arguments TDW is making in those slides are exactly the same arguments they are making today. The market is tight, we’re structurally short OSVs, day rates are rising and look how cheap we are if they continue to go up, etc. And TDW clearly believed what they were pitching: the stock spent most of the early ~2010s trading around $40-$50/share, and the company was taking their cash flow and aggressively buying back shares at those levels (see their 2013 10-k).

Tidewater filed for bankruptcy ~4 years later; their stock would be virtually wiped out (it would get a small tip of equity / warrants in the post reorg company), so the hundreds of millions they spent buying back shares were a better use of capital than lighting money on fire but it’s honestly a close call between the two.

History for TDW would again repeat in 2019. The three slides below are from TDW’s September 2019 deck, but you’d be forgiven for thinking they’re from TDW’s current investor decks. The arguments are the exact same to the ones they (and I) are making today: supply shortage and rising demand leading to increased utilization and rates.

So your big worry is that the offshore players are the companies who cried wolf. Every year they predict the cycle is tightening, that the supply dynamics are favorable, and that they’re going to earn a heck of a lot of cash…. and every year they turn out to be wrong. They especially turn out to be wrong when rates start to rise and everyone gets excited that the cash bonanza they’ve been waiting for is here…. and then oil prices collapse and everyone goes bankrupt again, or at minimum supply comes out of no where and floods the market and day rates never spike.

So I’m absolutely eyes wide open about this risk…. but I do think this time is different.

There are two ways to stop the offshore inflection point thesis: flood the market with supply, or destroy demand.

I’ve already talked a ton in part #2 about supply, so I won’t dive into that too deep here. But, to summarize, we’re ~10 years out from the last newbuild cycle. There’s simply no new or hidden source of supply left to come online; what we’re operating with today is what we’ve got for the next few years.

So we’re not going to have supply suddenly flood the market. That leaves a demand response to come in and destroy the thesis.

I talked about demand response in part #2, but I probably got a little too wonky on it.

The simple fact is this: if offshore is profitable, offshore vessels and drills will be in demand. The higher oil prices go, the more demand there is.

To break the demand side of the thesis, you need oil prices to drop. Remember, when you have a supply shortage (like I think we’re about to have / starting to have), your day rates are determined by the marginal profitability of drilling oil. Small decreases in oil price results in a lowering of that “cap” on day rates; larger decreases makes some offshore drilling unprofitable and decreases the demand for ships in general, which eventually will take the market from “demand outstrips supply” to “supply/demand equilibrium” or even return us to “limited offshore drilling; supply outstrips demand” (like we had the past ~decade).

So the question is how low can oil go before it starts to impact marginal day rates or overall demand for boats?

I’m going to attempt to answer that in a second, but before we do that, just keep one thing in mind: offshore drilling is a massive investment. Near term spot oil prices obviously factor into the thinking / economics behind it, but when companies are committing tens or hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars to offshore projects that have >decade long lives, they are doing it with an eye on out year oil prices, not the day to day fluctuations of spot year prices. I only point that out to emphasize that if you see a CNBC headline “oil down 10% (or up 10%) on (insert your preferred geopolitical event here”, it has some impact on supply / demand at the margin but it certainly doesn’t change the thesis (unlike with some nearer term oil/energy plays, where spot price swings can have massive implications for their cash flows and value).

I think the place to start answering the “when do low oil prices impact offshore demand” question is by noting that the current oil curve is plenty sufficient to drive the supply / demand dynamic tighter. RIG and VAL both announced new contracts recently with very nice day rates, and that jives with what I’ve heard from experts:

No diminished appetite for drilling based on recent oil price. I asked and talk to customers daily and a lot of the questions I focus on are do you have a concern about a recession, global recession, and impact on drilling plans, and a consistent answer is no.

And from management teams (below from the TDW management team on our podcast in early January):

So the momentum in day rate acceleration is continuing to increase and it's continuing to maintain itself. So we are very, very encouraged by the day rate environment around the world in all vessel classes.

That you’re seeing really strong rates at the current energy curve is important for my personal investment thesis / conviction. I have no view on oil prices higher or lower; if you put a gun to my head, I’d guess moderately higher in the near term just given China reopening, SPR releases ending, etc. But the energy market is massive and filled with very sophisticated traders. It’s not exactly a secret that the second largest economy in the world is reopening right as a mammoth SPR drawdown is ending / eventually reversing. It would shock me if the market wasn’t efficient enough to adjust for those two events!

Anyway, the slide below is from a recent VAL deck; it shows the rough oil breakeven for the offshore sector. You’ll see that >90% of projects are profitable with oil prices at $50-$55/barrel.

In talking to experts, that’s around the per barrel number that kept coming up where things would start to change. There was no definitive number, but most people I’ve talked to suggest offshore economics make sense and support continued strong day rate levels as long as oil stays above the $60 level in the out years. If it starts to go below that, big firms start to re-evaluate how much they want to put into offshore oil and you start running into the “marginal cost of oil caps offshore day rates” issues. One expert put it bluntly:

If you had, for whatever reason, the 5-year came at $50 or $55, I can promise you things would slow down markedly. You wouldn't have a cycle. But the question is more, why would we get there?

Again, I don’t have a view on where oil’s going…. but if the thesis starts to break down somewhere below $60 in the out years, I think you’ve got a pretty decent margin of safety at these levels. As I write this, oil is $70/barrel going 3-4 years out and still trading at ~$65/barrel into the 2030s.

So I think you’ve got a decent margin of safety here; things work really well if oil stays at current pricing or drifts down a little. If oil goes up, things work incredibly well. If oil drops, the thesis starts to come into question (though the nice thing about playing through unlevered players is that if the drop proves temporary you should have the staying power to make it through to the other end).

What could cause the long term world wide oil price to drop?

It’s pretty simple. The forward oil curve is the market’s best estimate of the long term supply/demand/cost construct of oil. The curve would be wrong (to the downside) if we had a major decrease in forecasted demand or increase in (cheap) supply.

On the demand side, you could change demand by reducing the need for oil and energy. That could come from a prolonged economic downturn (not a short term recession, but something that actually caused the need for energy to drop for a sustained period of time. Think a global depression / recession that lasted multiple years) or a shift to an alternative fuel source happening more quickly than the market’s factoring in. It’s hard for me to see either playing out; forecasting a sustained economic downturn seems pretty Malthusian, and, while I’m all for going green and reducing our reliance on fossil fuels, those changes take time and it’s tough to see them accelerating in such a way that collapses oil demand over the next decade. One expert put it succinctly:

But the reality is even those things are going to take so many years to roll out that I don't really see them as near-term threats, just collapse in oil price, collapse in demand, but that is so unlikely because we saw that collapse in demand through COVID, and we're still struggling to meet that demand across the world.

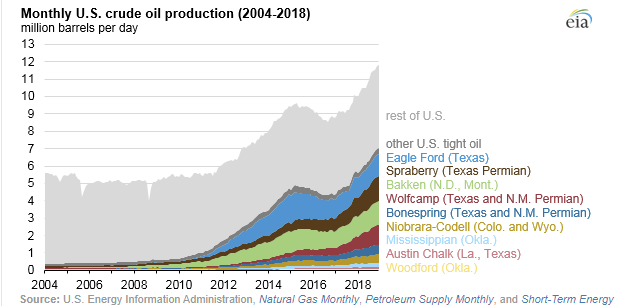

On the supply side, you could change the curve by suddenly finding a new, low cost source of oil. This is basically what happened in the 2010s: we thought the world was running short of low cost oil (remember peak oil in the late 2000s?), but the world suddenly discovered ~6m barrels/day of reasonably low cost production coming from U.S. shale oil. Global demand is something like 100m barrels/day, so having that much oil come online out of no where really changes the dynamics of the market!

For the price of futures curve for oil to be wrong today would basically take the world discovering a U.S. shale style cheap source of production over the next few years.

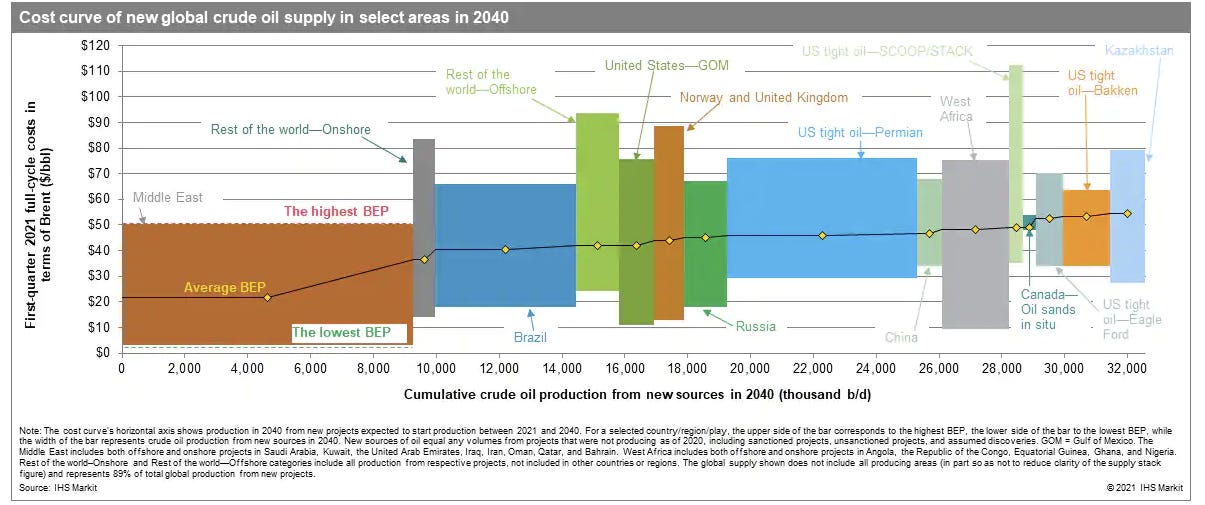

Just to dive in a little further into what the forward market is predicting on the supply / cost side, S&P has a piece forecasting global oil supply and cost out to 2040; you can see it below. If you think the forward price is wrong because of supply, you need to think one of the buckets below is too small (i.e. the middle east can produce 14m barrels/day at reasonable cost, not ~9m) or that there will be a new bar on that chart when someone runs it again in 2030/2040 (if you produced this chart ~15 years ago, the light blue “US Permian” source would not be on it!).

PS- that forward forecast of supply / price pretty much matches up with the current cost of production for different oil sources (below from a RIG 2020 deck; a little stale but it’s tough to find an up to the minute break down of global oil cost curves without paying a fortune).

So, for the supply side to be wrong, you need a new low cost source of oil to come on to really change the price forecast. It’s obviously not impossible (it already happened once in the last decade with U.S. Shale!), but I think it’s unlikely for a bunch of reasons: we’ve had years to find lower cost oil and haven’t found it, I’m not sure where we would find it at this point, etc. One critical point that I think is underdiscussed: even if we did find a new low cost source of oil, getting to it, extracting it, etc. would take a major investment and (depending on where the oil is) at least some political support for building the infrastructure (like pipelines) to exploit it. I’m not sure if any of that’s feasible in the current world unless energy prices are absolutely raging and we’re in a true energy shortage / crisis (i.e. I’m not sure politicians would love supporting a massive new development, and I’m very skeptical shareholders would give energy companies enough capital to fund that development). As a consumer, I’d be happy to be proven wrong on that skepticism though!

That’s the high level view of the main risk to the thesis (oil price dropping) and why I’m ok with the risk (I think you’ve got a good margin of safety at the current curve, I think the curve is reasonably efficient, and it’s hard for me to see a supply or demand shock big enough to drop through my margin of safety).

There is one other big risk to the offshore thesis; it can be nicely summed up with one image:

Ok, I jest (poorly). (PS- I think that story originally comes from Ben Graham, but I’ve seen it attributed to Buffett, or maybe it was from someone else. But I like to imagine the story was for sure created by a value investor who invested into an oil company cheaply only to see the company burn away all of their profits on overpriced acquisitions and leaning into wild and speculative drilling capex at the height of a cycle).

The other big bear thesis for offshore is that the inflection thesis is right, but the management teams are going to take their cash flow gusher and plow it back into new build boats, which will flood the market with supply and crush rates. Thus, investors will never see any of the current cash flow gusher, and it will end much quicker than rational economics would suggest it should.

There is some basis for this fear given this is exactly what happened in the mid-2010s bust (though falling oil prices thanks to shale played a role as well). Look at the slides below from TDW’s 2013 investor deck; they are bragging about bringing on 29 new build boats (>10% of their fleet size) right before the whole market is about to fall apart!

Anything can happen…. but I think the odds of offshore wrecking the cycle with a bunch of new builds is minimal for a bunch of reasons.

All of the management teams seem committed to returning capital to shareholders. Obviously management teams can lie, and facts can change, but I think they’ve all gotten religion (or at least they have it as long as day rates remain well below new build economics).

Speaking of new build economics, rates still remain well below new build economics, so I don’t think management teams will intentionally pursue something blatantly uneconomic.

Even if management teams wanted to pursue something crazy, most of these companies went through a restructuring process, and they now have pretty concentrated post-reorg shareholder bases with one or two financial / distressed focused investors having a nice sized stake. Each company also generally has a distressed / financial focused director or two on their board. If the management teams tried to do something uneconomic, I think the boards / shareholders would quickly slap them down.

If the management teams could somehow convince the boards to let them new build, they’d need to convince shipyards to build the boats. That would be a tall order in and of itself given I don’t think shipyards are equipped to do so…. but the real question is where would the money come from? After getting burnt last cycle, shipyards aren’t going to build boats on spec / without pretty solid down payments and guarantees from the vehicle owners. Where is all that cash going to come from? I doubt banks are lending to fund uneconomic newbuild in the near future!

So could a new build cycle happen and ruin the inflection? Theoretically, of course…. but I’m not sure how it practically could happen (and, even if it did, as I showed in part #2, the supply would be several years away, so you’d get a lot of cash in the short term though the market would certainly apply massive “bad capital allocation discounts” to any cash).

And just to emphasize: I don’t think management teams are even going to try it. In fact, I think it might be against management team’s interest to try a newbuild cycle. Consider TDW: 50% of management’s bonus is based on free cash flow (from their 2022 proxy). A new build cycle reduces free cash flow by increasing capex, so it’s largely against management’s near term interests (in the form of bonuses) to pursue a newbuild cycle (I used TDW as an example, but most other offshore companies have switched to something that encourages free cash flow or at least near term EBITDA).

At this point, I doubt we see a newbuild cycle unless the new build returns got so good that investors begged boards to start building, and boards went out and changed management incentives to encourage them to build. I think it’s much more likely that we see management teams stick to what they’ve been doing / saying since the current cycle started to swing up: look to buy up distressed smaller competitors at attractive valuations, and return cash aggressively to shareholders if they can’t do that.

Ok, that does it for the bear thesis. I’m going to conclude the series by walking through some random thoughts that didn’t quite fit into the series so far / responding to some extra questions and feedback I got on the first two parts of the series / pasting few extra quotes from experts that I thought were interesting but couldn’t squeeze in to the series so far.

Odds and ends

I had largely finished writing this article by the weekend… and then the FT published a really lengthy look into the US shale revolution and how it appears to be slowing over the weekend. It’s quite good, and has big implications for the worldwide supply dynamic for oil (in line with what I talked about in the article). Since it generally jives with what I discussed early, I figured I’d link it here instead of rewriting portions of the article!

Why all the focus on Tidewater (TDW): I kicked off the series with two podcasts on TDW (episode #146 (with Tidewater’s management) and episode #147 (with Judd Arnold)), and I returned to TDW a lot during the series. TDW does OSVs, and basically every other publicly traded player focuses on drilling (VAL, RIG, DO, NE, etc.). Why so much focus on TDW?

From an investing standpoint, I just like them a little more than the other plays. I know plenty of investors who are very knowledgeable on the offshore space who disagree with me! But, personally, I like TDW’s management team, I think they are more open than the drillers (which lets their earnings respond quicker to rising day rates), and I just find OSVs a little easier to think about than drillers.

One other thing I like about TDW? Bob Robotti (a friend of the pod!) is the company’s second largest shareholder and on the board. Having a respected value investor be a large shareholder and on the board is nice but not wildly notable in the grand scheme of investing; what is notable about this case is that Bob has been aggressively buying shares basically every time the insider window for buying shares is open (or at least that’s what it appears to me!). Robotti is a 13F filer (you can see his most recent here); TDW is a massive holding for him (>15% of assets; the second largest position behind BLDR). Could Robotti be wrong on TDW? Of course! Could the cycle turn unexpectedly? Sure! But having him on the board and continuing to buy despite an already oversized position gives me confidence that the story management is pitching is the story the board is hearing as well, that there aren’t any wild near term issues that are going to pop up, and that capital allocation is going to be on point here. Again, all of that could be wrong, but that’s how I think about it!

Aside from “what’s the bear case” for offshore (or emails explaining the bear case to me!), the most frequent question I got on this series is “why not just buy a small cap oil company / what’s the opportunity cost of offshore versus other oil plays?” My responses could all be completely wrong, but they are below:

For the most part, direct oil plays are very sensitive to the near term price of oil; I don’t think you have that super sensitivity with offshore (even though that is how they trade sometimes!).

I like that (in my mind) you’re buying offshore with a little cushion / margin of safety versus the curve dropping. Oil prices go up and offshore rates should scream high. Oil prices stay around here and rates probably tick up a little bit. Oil prices drop a bit and rates probably stabilize but these companies still print cash. You really need oil prices to plummet to lose here; I’m not aware of a ton of oil companies with that type of skewed risk/reward.

Oil companies introduce some geology / asset specific risk (a well going dry, a spill, etc.). Similar type risk is not impossible for offshore but it’s a much more remote risk.

Supply response for offshore is much, much harder than supply response for oil as a whole. It takes at least two years to build a new ship. It takes a matter of weeks to get a few extra wells online. I think offshore gives you more super-normal cycle profit potential, but that’s probably splitting hairs.

Offshore probably has less political risk (oil prices scream higher and you might get windfall taxes on oil companies; try to do that to a boat and the boat just sails to the next country over!).

I feel comfy that the management teams for offshore “get it” (i.e. won’t go on a wild building spree / will return capital to shareholders). I’m not as comfy with that for most energy teams.

The way most investors like to value cyclical businesses is by figuring out what a mid-cycle rate is and then slapping a multiple on it. Investors generally mean mid-cycle rates as what the company will earn when their market is not at the top or bottom of the cycle. As I’ve come to think about the industry, I’m not sure that’s really the right way to think about offshore, but for what it’s worth here’s what one expert responded when I asked what are mid-cycle rates?

I'd take 400 all day long. That's kind of like a mid-cycle average. I think a lot of people see a mid-four as a more realistic mid-cycle number, we don't need it. So I don't want to kind of anchor to that. We're literally printing money at 400. And I don't need to be greedy. It's great if we're there, but I don't think we need it. As long as the rest of the supply chain doesn't get all out of whack and everyone has healthy return. That is a number that is tolerable. It supports the lion's share of all offshore drilling projects. It's a number that don't cause operators to buckle too much. And then we make money. And so it's not a number that is just such a stretch for anybody.

Why don’t I think “mid-cycle earnings” is the right way to look at it? I think it was the shipping man that talked about shipping as a business where you lose money for nine years and then in the tenth year things get really tight and you make wild profits, and as an investor you basically just want to make sure you’re buying cheaply enough to eventually capture that wild profit cycle and cover your cost basis and all of the losses to get there. Given the supply / demand for offshore, something like that is probably the directionally correct way to think about offshore as well, though there are certainly some differences given contract lengths, how long it takes for a supply response to show up, how reliant it is on oil prices, etc.

There are two long term use cases for OSVs and drillers that don’t involve oil. For OSVs, they can be used for supporting offshore wind. Drillers could be used for carbon capture in the long run; basically, you would just “capture” carbon and reverse the process for extracting oil from under the ground (instead depositing / storing that CO2; OSVs would benefit here as they’d still be required to support the drillers injecting CO2). Both are interesting use cases and could really support the terminal life of these assets…. but they’re big question marks. The stocks / assets are so cheap that I think the market is assigning negative terminal value to them; wind and carbon capture extending their lives would just prove to be a nice cherry on top. Here’s what one expert had to say on carbon capture in the long run for drillers:

We talked about the fact that post 2040, we don't know what happens to those rigs. Well, carbon capture is an interesting thing. It looks like the best place to store CO2 is in a reservoir…. You probably need reservoir that are full of water today. Because you put the CO2 in and they push in the water. Because if you're using an existing oil reservoir, there is perforation already. So CO2 can bubble out, I'm being cautious. But it could mean that you have a brand-new lease of life for these assets, which suddenly start drilling, maybe talking late 2020s, they start drilling again.

I mentioned that, if demand for offshore assets is outstripping supply, then the limit on day rates is the marginable profitability of wells. That does not mean that in a hot enough environment offshore asset owners can’t extract more concessions from oil companies. If the cycle runs hard enough, eventually what is going to happen is energy companies will start offering other concessions to offshore owners. In particular, you’ll see energy companies start giving out longer and longer contracts to lock in ships and guarantee that their assets will be producing (in fact, there’s some signs of this already happening; here’s an article from over the weekend noting that we’re starting to see longer term contracts get signed). Here’s how one expert described how negotiations evolve as offshore goes from oversupply to getting tight:

when supply is there, capacity is there, oil companies have the ability to go out and say, look, I want this, and I want that. I want it here and I want it for just a short period of time, and then I want to take a break and then I'm going to do this, and I want you to come back. They dictate both to some extent, the commercial elements but also the terms and conditions.

And I think a lot of folks discount how important a well-structured contract is and the protections that are afforded in a well-structured contract. And those things, it goes in lockstep with rates, and you're basically beholden, stack a rig or just suck it up and accept it. That pendulum is coming back very, very quickly in our favor.

And you're right, when they have a bunch of options, they go and tinder it, everybody gets desperate and starts cutting throat to race to the bottom. When things are tighter as they are now, operators say, okay, look, this isn't good. No, I really want this rig because I need this technical feature, that technical feature. I need MPD, dual BOP, all these different things that can be somewhat unique across the rig fleet.

And so they're kind of forced to go directly and directly negotiate with the drilling contractor and say, all right, look, we want rig X, Y, Z. We're only going to talk to you. Let's hammer on a deal. So we're seeing a whole lot more of that. That is somewhat of a unique dynamic that's probably evolved in the last three to six months.

I mentioned in part two how difficult it will be to build new offshore assets; here’s a nice quote from an expert what the process for newbuilds would look like:

I was sitting down with a couple of drilling CEOs and board members last week in London. I asked one of these guys, "How much will it cost to order new ultra-deepwater rig, brand-new?" Because we haven't seen any orders. So we don't know what price it is. These guys, because they're private, they can do whatever they want. So they regularly ask for quotes. And they got a quote for a two-rig order, which they don't intend to place, for close to $1 billion. It was $825 million. But then by the time you put all the spares, pipes and different other items necessary for the startup, you got to close to $1 billion in the water. Now imagine what kind of day rates you need for that. So new capacity isn't coming from new build. That's the first thing.

When they were asking for two rigs just to see if the yard, you asked for a package, right, because yards don't like to build one unit. It becomes very expensive because you normally make mistake for the first one. So you have to give them at least two and ideally four, just a little thing.

There's a learning curve that's pretty steep, and they haven't built any for several years. And that's why one rig, they probably wouldn't even answer you for one rig. But yes, the single unit was close to $1 billion in the water. So no new rigs there. You can reactivate, these days, we're probably talking to close to $100 million to reactivate.

You can do the math. If you think about $200,000 margin per day on your rig, $200,000 to $400,000 to keep it super simple, $100 million takes a hell of a lot of time. I mean, you're probably talking about 15 months payback on the margin itself. I know my old company was saying 12, so okay, I'll take that number. They're good people. But it's hard to do it unless a client is ready to pay for it.

These are all big numbers. So I think there, it's probably going up. Where I'm getting a bit scared is, are we about to see $500,000, $600,000 rates again? We've said we'd never see them again. It's not impossible. We just have to go higher to keep taking rigs out of cold stack. Warm stack, fine, that's easy. But cold stack, you need to go higher than $400,000.

All you have to give is a very long contract, like five years, which it feels like the companies are not ready to do, and there's some accounting issue in doing it. If you do give a contract that's too long, it might show up as debt on your balance sheet as the oil company. You'd be careful of that. So yes, you probably have to pay a high rate.

If you asked me to choose one presentation to best understand the offshore thesis, it would undoubtedly be this presentation from Transocean in February 2020. Why? Because I think it does the best job of outlining the offshore thesis (shale supply growth slowing, oil offshore break-evens decreasing, asset shortage as old asset retire and no new growth, and tons more; I wish they still did their presentations in that format!) and because the timing (literally days before COVID became a full blown crisis and sent oil negative) is so comical that it illustrates how quickly the cycle can turn and how exposed to external shocks the whole industry is!

Thank you for the write up. Have you taken a look at Gulf Marine Services listed on the LSE?

Thanks,

Josh

Thanks for this. Thoroughly enjoyed the 3 articles. My takeaway - this belongs to Buffett's 'Too Hard' pile. You'll have to deal with supply (capex cycles, cashflows, contracting, utilisation rates), and demand (policies/politics, oil demand)...too hard...maybe an oil royalty company to gain exposure to this space would be much easier with less risk